Last month we discussed the controversy regarding the recent revelation that, back in 2015, economist Alan Krueger had been paid $100,000 by Uber to coauthor a research article that was published at the NBER (National Bureau of Economic Research, a sort of club of influential academic economists) and seems possibly to have been influential in policy.

Krueger was a prominent political liberal—he worked in the Clinton and Obama administrations and was most famous for research that reported positive effects of the minimum wage—so there was some dissonance about him working for a company that has a reputation for employing drivers as contractors to avoid compensating them more. But I think the key point of the controversy was the idea that academia (or, more specifically, academic economics (or, more specifically, the NBER)) was being used to launder this conflict of interest. The concern was that Uber paid Krueger, the payment went into a small note in the paper, and then the paper was mainlined into the academic literature and the news media. From that perspective, Uber wasn’t just paying for Krueger’s work or even for his reputation; they were also paying for access to NBER and the economics literature.

In this new post I’d like to address a few issues:

1. Why now?

The controversial article by Hall and Krueger came out in 2015, and right there it had the statement, “Jonathan Hall was an employee and shareholder of Uber Technologies before, during, and after the writing of this paper. Krueger acknowledges working as a consultant for Uber in December 2014 and January 2015 when the initial draft of this paper was written,” is not “an adequate disclosure that Uber paid $100,000 for Krueger to write this paper.”

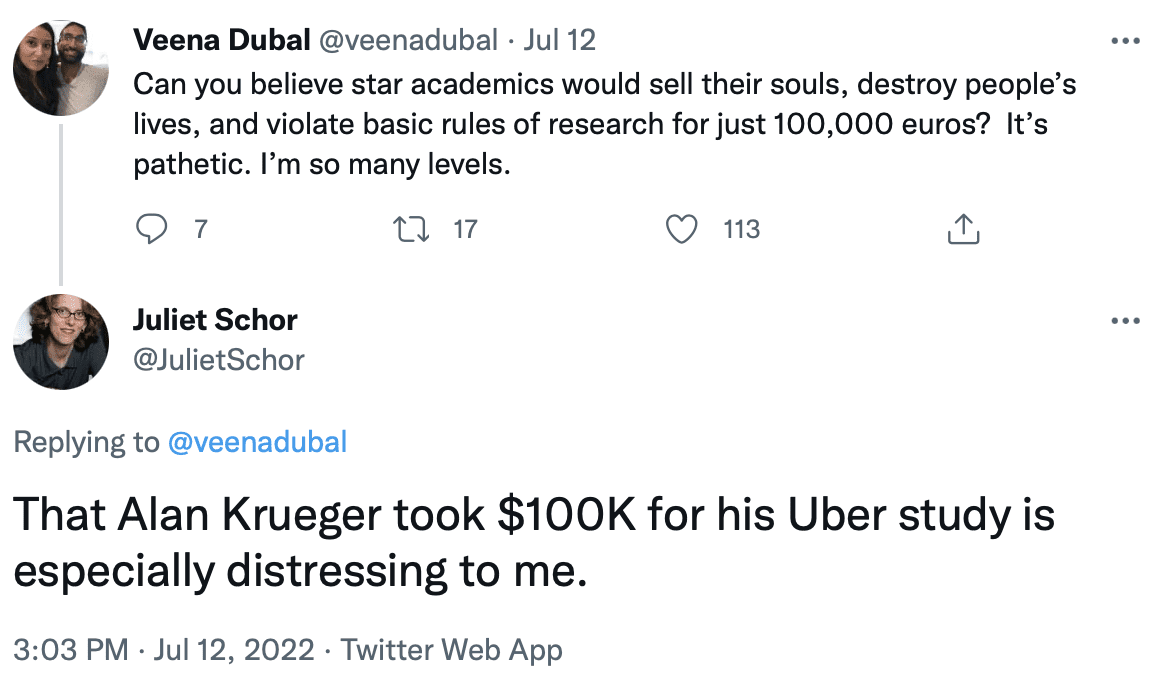

So why the controversy now? Why are we getting comments like this now:

rather than in 2015?

The new information is that Krueger was paid $100,000 by Uber. But we already knew he was being paid by Uber—it’s right on that paper. Sure, $100,000 is a lot, but what were people expecting? If Uber was paying Krueger at all, you can be pretty sure it was more than $10,000.

I continue to think that the reason the controversy happened now rather than in 2015 is that, back in 2015, there was a general consensus among economists that Uber was cool. They weren’t considered to be the bad guy, so it was fine for him to get paid.

2. The Necker cube of conflict of interest

Conflict of interest goes in two directions. On one hand, as discussed above, there’s a concern that being paid will warp your perspective. And, even beyond this sort of bias, being paid will definitely affect what you do. Hall and Krueger could be the most ethical researchers in the universe—but there’s no way they would’ve done that particular study had Uber not paid them to do it. This is the usual way that we think about conflict of interest.

But, from the other direction, there’s also the responsibility, if someone pays you do to a job, to try to do your best. If Hall and Krueger were to take hundreds of thousands of dollars from Uber and then turn around and stab Uber in the back, that wouldn’t be cool. I’m not talking here about whistleblowing. If Hall and Krueger started working for Uber and then saw new things they hadn’t seen before, indicating illegal or immoral conduct by the company, then, sure, we can all agree that it would be appropriate for them to blow the whistle. What I’m saying is that it, if Hall and Krueger come to work for Uber, and Uber is what they were expecting when they took the job, then it’s their job to do right by Uber.

My point here is that these two issues of conflict of interest go in opposite directions. As with that Necker cube, it’s hard to find a stable intermediate position. Is Krueger an impartial academic who just happened to take some free money? Or does he have a duty to the company that hired him? I think it kind of oscillates between the two. And I wonder if that’s one reason for the strong reaction that people had, that they’re seeing the Necker cube switch back and forth.

3. A spectrum of conflicts of interests

Another way to think about this is to consider a range of actions in response to taking someone’s money.

– At one extreme are the pure hacks, the public relations officers who will repeat any lie that the boss tells them, the Mob lawyers who help in the planning of crimes, the expert witnesses who will come to whatever conclusion they’re paid to reach. Sometimes the hack factor overlaps with ideology, so you might get a statistician taking cash from a cigarette company and convincing himself that cigarettes aren’t really addictive, or a lawyer helping implement an illegal business plan and convincing himself that the underlying law is unjust.

– Somewhat more moderate are the employees or consultants who do things that might otherwise make them queasy, because they benefit the company that’s paying them. It’s hard to draw a sharp line here. “Writing a paper for Uber” is, presumably, not something that Krueger would’ve done without getting paid by Uber, but that doesn’t mean that the contents of the paper cross any ethical line.

– Complete neutrality. It’s hard for me to be completely neutral on a consulting project—people are paying me and I want to give them their money’s worth—but I can be neutral when evaluating a report. Someone pays me to read a report and I can give my comments without trying to shade them to make the client happy. Similarly, when I’ve been an expert witness, I’ve just written it like I see it. I understand that this will help the client—if they don’t like my report, they can just bury it!—so I’m not saying that I’m being neutral in my actions. But the content of my work is neutral.

– Bending over backward. An example here might be the admirable work of Columbia math professor Michael Thaddeus in criticizing the university’s apparently bogus numbers. Rather than going easy on his employer, Thaddeus is holding Columbia to a high standard. I guess it’s a tough call, when to do this. Hall and Krueger could’ve taken Uber’s money and then turned around and said something like, This project is kinda ok, but given the $ involved, we should really be careful and point out the red flags in the interpretation of the results. That would’ve been fine; I’ll just say again that this conflicts with the general attitude that, if someone pays you, you should give them your money’s worth. The Michael Thaddeus situation is different because Columbia pays him to teach and do research; it was never his job to pump up its U.S. News ranking.

– The bust-out operation. Remember this from Goodfellas? The mob guys take over someone’s business and strip it of all its assets, then torch the place for the insurance. This is the opposite of the hack who will do anything for the boss. An example here would be something like taking $100,000 from Uber and then using the knowledge gained from the inside to help a competitor.

In a horseshoe-like situation, the two extremes of the above spectrum seem the least ethical.

4. NBER

This is just a minor thing, but I was corresponding with someone who pointed out that NBER working papers are not equivalent to peer-reviewed publications.

I agree, but NBER ain’t nothing. It’s an exclusive club, and it’s my impression that an NBER paper gets attention in a way that an Arxiv paper or a Columbia University working paper or an Uber working paper would not. NBER papers may not count for academic CV’s, but I think they are noticed by journalists, researchers, and even policymakers. An NBER paper is considered legit by default, and that does have to do with one of the authors being a member of the club.

5. Feedback

In an email discussion following up on my post, economics journalist Felix Salmon wrote:

My main point the whole time has just been that if Uber pays for a paper, Uber should publish the paper. I don’t like the thing where they add Krueger as a second author, pay him $100k for his troubles, and thusly get their paper into NBER. Really what I’m worried about here is not that Krueger is being paid to come to a certain conclusion (the conflict-of-interest problem), so much as Krueger is being paid to get the paper into venues that would otherwise be inaccessible to Uber. I do think that’s problematic, and I don’t think it’s a problem that lends itself to solution via disclosure. On the other hand, it’s a problem with a simple solution, which is just that NBER shouldn’t publish such papers, and that they should live the way that god intended, which is as white papers (or even just blog posts) published by the company in question.

As for the idea that conflict is binary and “the conflict is there, whether it’s $1000 or $100,000” — I think that’s a little naive. At some point ($1 million? $10 million? more?) the sheer quantity of money becomes germane. . . .

Salmon also asked:

Is there a way of fixing the disclosure system to encompass this issue? It seems pretty clear to me that when the lead author is literally an Uber employee, Uber has de facto control over whether the paper gets published. Again, I think the solution to this problem is to have Uber publish the paper. But if there’s a disclosure solution then I’m interested in what it would look like.

I replied:

You say that Uber should just publish the paper. That’s fine with me. I will put a paper on my website (that’s kinda like a university working paper series, just for me), I will also put it on Arxiv and NBER (if I happen to have a coauthor who’s a member of that club), and I’ll publish in APSR or JASA or some lower-ranking journal. No reason a paper can’t be published in more than one “working paper” series. I also think it’s ok for the authors to publish in NBER (with a disclosure, which that paper had) and in a scholarly journal (again, with a disclosure).

You might be right that the published disclosure wasn’t enough, but in that case I think your problem is with academic standards in general, not with Krueger or even with the economics profession. For example, I was the second author on this paper: where the first and last authors worked at Novartis. I was paid by Novartis while working on the project—I consulted for them for several years, with most of the money going to my research collaborators at Columbia and elsewhere, but I pocketed some $ too. I did not disclose that conflict of interest in that paper—I just didn’t think about it! Or maybe it seemed unnecessary given that two of the authors were Novartis employees. In retrospect, yeah, I think I should’ve disclosed. But the point is, even if I had disclosed, I wouldn’t have given the dollar value, not because it’s a big secret (actually, I don’t remember the total, as it was over several years, and most of it went to others) but just because I’ve never seen anyone disclose the dollar amount in an acknowledgements or conflict-of-interest statement for a paper. It’s just not how things are done. Also I don’t think we shared our data. And our paper won an award! On the plus side, it’s only been cited 17 times so I guess there’s some justice in the world and vice is not always rewarded.

I agree that conflict is not binary. But I think that even with $1000, there is conflict. One reason I say this is that I think people often have very vague senses of conflict of interest. Is it conflict of interest to referee a paper written by a personal friend? If the friend is not a family member and there’s no shared employment or $ changing hands, I’d say no. That’s just my take, also my approximation to what I think the rules are, based on what Columbia University tells me. Again, though, I think it would’ve been really unusual had that paper had a statement saying that Krueger had been paid $100,000. I’ve just never seen that sort of thing in an academic paper.

Did Uber have the right to review the paper? I have no idea; that’s an interesting question. But I think there’s a conflict of interest, whether or not Uber had the right to review: these are Uber consultants and Uber employees working with Uber data, so no surprise they’ll come to an Uber-favorable conclusion. I still think the existing conflict of interest statement was just fine, and that the solution is for all journalists to report this as, “Uber study claims . . . ” The first author of the paper was an Uber employee and the second author was an Uber consultant—it’s right there on the first page of the paper!

As a separate issue, if the data and meta-data (the data-collection protocol) are not made available, then that should cause an immediate decline of trust, even setting aside any conflict of interest. I guess that would be a problem with my above-linked Novartis paper too; the difference is that our punch line was a methods conclusion, not a substantive conclusion, and you can check the methods conclusion with fake data.

Salmon replied:

If you want the media to put “Uber study claims” before reporting such results, then the way you get there is by putting the Uber logo on the top of the study. You don’t get there by adding a disclosure footnote and expecting front-line workers in the content mines to put two and two together.

As discussed in my original post on the topic, I have lots of conflicts of interest myself. So I’m not claiming to be writing about all this from some sort of ethically superior position.

6. Should we trust that published paper?

The economist who first pointed me to this story (and who wished to remain anonymous) followed up by email:

I’m surprised that the focus of your thoughts and of the others who commented on the blog were on whether Krueger acted correctly, not on what to do with the results they (and others) found. I guess my one big takeaway from now on is to move my priors more strongly towards being sceptical of papers using non-shared, proprietary data…

That’s a good point! I don’t think anyone in all these discussions is suggesting we should actually trust that published paper. The data were supplied by Uber; the conclusions were restricted to what Uber wanted to get; the whole thing was done in an environment where economists loved Uber and wanted to hear good things about it; etc.

I guess the reason the conversation was all about Krueger and the role of academic economics was that everyone was already starting from the position that the paper could not be trusted. If it were considered to be a trustworthy piece of research, I think there’d be a lot less objection to it. It’s not like the defenders of Krueger were saying they believed the claims in the paper. Again, part of that is political. Krueger was a prominent liberal economist, and now in 2022, liberal economists are not such Uber fans, so it makes sense that they’d defend his actions on procedural rather than substantive grounds.

Felix’s comments touch on a point I made on your previous post. The problem is not that Krueger got paid. The problem is what Uber was paying for. They were not paying for his expertise. They were paying him to launder their data into the respectable academic and public policy discourse.

If the data are ‘clean’–I guess no problem? A win-win. Uber gets some legitimate results into the academic sphere, Krueger gets a paper and some money, and we are all better informed (maybe, maybe not)?

The reason why the size of the payment here is “germane” is that it seems reasonable that the cleanliness of the data is inversely correlated with the amount of the laundering fee. You need to really shell out the big bucks to get a big name to attach his reputation and ask no questions if something smells wrong. If everything is on the up and up, presumably you would not have to pay as much.

From the standpoint of research and public policy, it also a bit worrying that publication bias may also be explicitly attached to a buy-in fee (e.g. p-hack your way to a good data snapshot + pay enough up front to get a big name to publish it).

Talk about a buried lede (in the penultimate paragraph): “I don’t think anyone in all these discussions is suggesting we should actually trust that published paper.”

Seems like this is a case in which the system worked just fine, so I’m not sure how much there is to learn from this example.

A recurring theme on this blog is that we shouldn’t presume the conclusion of a paper is accurate just because of the fact that it was published, or where it was published. That’s what post-publication review (such as this blog) is for.

It’s also worth noting that this paper was published in a peer-reviewed journal in 2017. Why is it still being referred to as an NBER working paper? Twitter thrives on manufactured outrage.

Should we trust the paper? It’s a survey of Uber drivers asking them why they’re driving for Uber. Turns out, they like extra income. And they like driving for Uber more than not driving for Uber, which we can be pretty confident about, given that they were driving for Uber at the time of the survey.

David:

The NBER thing is relevant because it’s my impression that the article was influential before it appeared in the peer-reviewed journal. Indeed, I think NBER working papers can get more attention than published papers outside the top few journals. Also, there’s a lot more to the paper than your summary. Here’s the abstract:

> Salmon replied:

>

> If you want the media to put “Uber study claims” before reporting such results, then the way you get there is by putting the Uber logo on the top of the study. You don’t get there by adding a disclosure footnote and expecting front-line workers in the content mines to put two and two together.

Salmon seems to have a pretty dim opinion of the journalists reporting on these kinds of papers. Is someone who cannot understand affiliations and disclosure footnotes qualified to read and summarize the findings? Again, even setting aside Krueger’s disclosure, his co-author, Hall, had an Uber affiliation. It would be pretty naive to assume a paper coauthored by someone at Uber might not have been influenced by the company line. Alerted to that fact, it’s not hard to then check the disclosure notice.

Indeed. The media seems to have no trouble reporting other studies as “a Harvard study” or “research by professors at Stanford”, even when a Harvard or a Stanford logo is not included. Hard to see why the rules should be different for a study of this kind. Should a study with a co-author who works in the government have the United States flag imprinted on the title page?

I can see why a journalist looking to quickly summarize a paper might miss the fine print, but it seems to me that says more about journalism than the original research. Especially as, in so many other cases not involving a conflict of interest, we have still seen the media mischaracterize the claims of researchers.

A noted aspect of statistics is the so-called “file drawer problem.” Unfavorable and/or boring stuff never sees the light of day. If this Kreuger/Uber study had shown the organization in a negative way, does one really think a paper would have been submitted to NBER for all to see?

Once again, I am no more paranoid than the next man, provided the next man is Richard Nixon. However, it stretches credulity to believe that this study would ever get into print if Uber would appear in less than a positive light.

agreed. krueger may have been compensated in part for a “buy -> bury option” on the paper.

It’s a bit hard for me to see the difference between $ conflicts of interest and other kinds of COI. Many including this blog have noted the problems of the garden of forking paths and p-hacking to select “positive” or “interesting” results, a consequence of the fact that these results lead to career advancements in academia i.e. being an academic wanting awards/tenure/promotion is itself arguably a COI. As is political ideology – if a researcher arrives at a conclusion that they don’t like they may bury the study or continually use their researcher degrees of freedom until they arrive at an agreeable result.

Why is the concern of $ COI so much more emphasized than the others? I mean this genuinely and not in a rhetorical way. Is it that we need to draw a line somewhere and $ is an easy line to draw since it’s material rather than abstract? Is it that everyone has the other two COI so it’s pointless to keep pointing it out while $ is an exceptional case? Is it that the effect of $ is so much greater than other COI?

I could also care less. So many people are already doing questionable stuff “to survive” that the right way to read a paper is assume it was written by the weaseliest person you’ve ever met. If that isn’t how read a paper in fields like biomed, well… sorry you are doing it wrong.

Eg, take a random finding from cancer or spinal cord injury research. There is about 75% chance it would not survive a replication even using the weak criteria of producing results “significant in the same direction”. In many cases, repeating the experiment was not even possible in principle.

https://elifesciences.org/articles/71601

https://elifesciences.org/articles/67995

It is not usually outright lying, but very selective design, reporting, and analysis. This culture also selects for people following standardized rituals, because they can produce some kind of output while having no idea they are even doing something wrong.

This is the scandal we should be concerned with.

I come at this from the perspective of one who spent most of his career in the biopharma industry. I took a lot of grief over the years doing media defending pharma-sponsored research. I was also one of the two principal staffers that developed the PhRMA Principles for the Conduct of Clinical Trials and Communication of Clinical Trial Results (you can google the title to get the document). One of the key things that we constantly stressed was disclosure of funding sources.

One can find conflicts everywhere. Kreuger was retained as a consultant by Uber to go over some research and write a paper. For this he was compensated. I have not seen anything about how the terms were agreed upon nor the actual contract itself in terms of publication rights. Perhaps Uber offered $100K up front. Perhaps Kreuger thought this was way too much but if they were willing to pay this amount, so be it. Unless someone has specific knowledge of what was in the contract, folks should not cast specific aspersions.

Pharma companies sponsor lots of clinical trials and agreements on publication rights are always negotiated up front. Data disclosure is handled by the medical journals. I’ll only ad a final anecdote. Back in the late 1960, Roche set up an Institute of Molecular Biology on their corporate campus and hired some world class academic researchers to join. At the time the company had two of the four best selling drugs in the US (Valium & Librium). The Institute’s scientists published research in world class journals and none of that work was ever impugned despite funding in part coming from Roche (scientists could continue to get funding from NIH). there has always been a lot of industry funded research going on in the US and it can be done in an appropriate manner.

You may have to be more specific because the research produced by Roche on benzodiazepines was definately later impugned. They were accused of suppressing data, etc in one of the largest lawsuits ever. Eg:

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm199899/cmselect/cmhealth/549/99072723.htm

However, I think if you looked into a typical academic lab funded by government grants, you are likely find the same behaviour. Not as well funded, but there.

With appropriate apologies and plagiarism alerts.

Uber: would your write a paper for us for $1,000,000?

Economist: I’d certainly consider it.

Uber: would you write a paper for us for $100?

Economists: What! What sort of a professional do you think I am?

Uber: We have already determine what you are. Now we are just negotiating a price.

$100 seems like a very small amount for an economist of Krueger’s stature. If that isn’t worth less than his time writing the paper, then he must hardly be spending any time on it.

Off the main topic of this post but I had forgotten about Necker cubes and had to look that up. Reminded me that many, many years ago (probably like the dawn of the stone age) I was seeing a girl attending an Art College and one week she had an assignment to create a painting with a reversible background (Escher of course did any number of these). Both my friend, and the class as a whole, came up with some pretty neat patterns. The Necker cube reminded of that (and i took me awhile looking at the Wikipedia page to see both patterns they claimed you could see). Or put another way, a famous but rather boring (to me) history professor from whom I took a class had as a mantra that “where you stand depends on where you sit.”

> Sure, $100,000 is a lot, but what were people expecting?

I think this kind of misses the point, which is that much of the outrage is that he was so cheap to buy… Like if you paid him $20M people would understand, but “selling your soul” for less than 1 yr salary for a professor is what’s making people incredulous. Why are economists so cheap?

“much of the outrage is that he was so cheap to buy”

That’s a comical explanation! Are you seriously claiming that he’d be off the hook if he took $20M instead of $0.1M? :)

To the extent that there is “outrage”, its mostly hot air turning the readership turbine. Just like the Chetty et. al. paper, no one should take a single paper as the green light for any kind of policy.

No, just that people wouldn’t be so incredulous. I shouldn’t have said outrage, I meant something more like shock.

The problem with the disclosure is not that it didn’t mention the amount, but that it didn’t mention what he was consulting for. If, indeed, he was paid $100,000 to write that paper, he wasn’t just “consulting for Uber”, he was being paid by Uber to write that paper. That’s hugely different from, “I’ve done work off and on for Uber over the years,” which is how I would have interpreted what he said.

Was Hall paid to write the paper too? Nobody’s touched on that.