“Not replicable, but citable” is how Robert Calin-Jageman puts it. His colleague Geoff Cumming tells the story:

The APS [Association for Psychological Science] has just given a kick along to what’s most likely a myth: The Lucky Golf Ball. Alas!

Golf.com recently ran a story titled ‘Lucky’ golf items might actually work, according to study. The story told of Tiger Woods sinking a very long putt to send the U.S. Open to a playoff. “That day, Tiger had two lucky charms in-play: His Tiger headcover, and his legendary red shirt.”

The story cited Damisch et al. (2010), published in Psychological Science, as evidence the lucky charms may have contributed to the miraculous putt success.

Laudably, the APS highlights public mentions of research published in its journals. It posted this summary of the Golf.com story, and included it (‘Our science in the news’) in the latest weekly email to members.

However, this was a misfire, because the Damisch results have failed to replicate, and the pattern of results has prompted criticism of the work. . . .

The original Lucky Golf Ball study

Damisch et al. reported a study in which students in the experimental group were told—with some ceremony—that they were using the lucky golf ball; those in the control group were not. Mean performance was 6.4 of 10 putts holed for the experimental group, and 4.8 for controls—a remarkable difference of d = 0.81 [0.05, 1.60]. (See ITNS, p. 171.) Two further studies using different luck manipulations gave similar results.

The replications

Bob and colleague Tracy Caldwell (Calin-Jageman & Caldwell, 2014) carried out two large preregistered close replications of the Damisch golf ball study. Lysann Damisch kindly assisted them make the replications as similar as possible to the original study. Both replications found effects close to zero. . . .

The pattern of Damisch results

The six [confidence intervals in the original published study] are astonishingly consistent, all with p values a little below .05. Greg Francis, in this 2016 post, summarised several analyses of the patterns of results in the original Damisch article. All, including p-curve analysis, provided evidence that the reported results most likely had been p-hacked or selected in some way.

Another failure to replicate

Dickhäuser et al. (2020) reported two high-powered preregistered replications of a different one of the original Damisch studies, in which participants solved anagrams. Both found effects close to zero.

All in all, there’s little evidence for the lucky golf ball. APS should skip any mention of the effect.

I can’t really blame the authors of the original study. 2010 was the dark ages, before people fully realized the problems with making research claims by sifting through “statistically significant” comparisons. Sure, we realized that p-values had problems, and we knew there were ways to do better, but we didn’t understand how this mode of research could not just exaggerate effects and lead to small problems but could allow researchers to find patterns out of absolutely nothing at all. As E. J. Wagenmakers put it a few years later, “disbelief does in fact remain an option.”

I can, however, blame the leaders of the Association for Psychological Science. To promote work that failed to replicate, without mentioning that failure (or the statistical problems with the original study), that’s unscientific, it’s disgraceful, it’s the kind of behavior I expect to see from the Association for Psychological Science. So I’m not surprised. But it still makes me sad. I know lots of psychology researchers, and they do great work? Why can’t the APS write about that? Why can’t they write about the careful work of Calin-Jageman and Caldwell? This is selection bias, a Gresham’s law in which the crappier work gets hyped. Not a good look, APS.

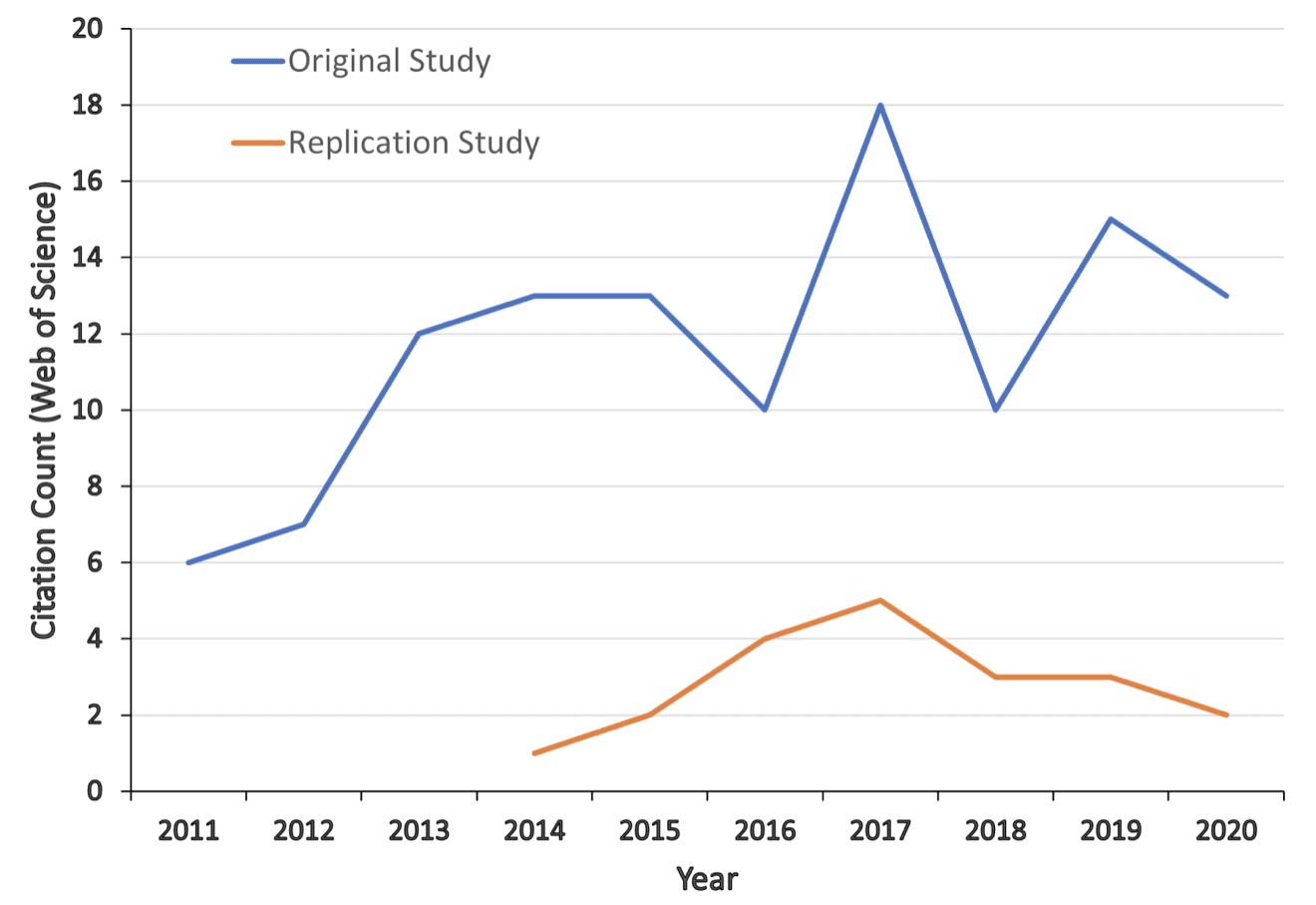

As to Golf.com, sure, they fell down on the job too, but I can excuse them for naively thinking that a paper published in a leading scientific journal should be taken seriously. As the graph above shows, this problem of citing unreplicated work goes far beyond Golf.com.

I get that the APS made a mistake in 2010 by publishing the original golf ball paper. Everybody makes mistakes. But to promote it ten years later, in spite of all the failed replications, that’s not cool. They’re not just passively benefiting from journalists’ credulity; they’re fanning the flames.

Golf: No big deal?

Yeah, sure, golf, no big deal, all in good fun, etc., right? Sure, but . . .

1. The APS dedicated a chunk of space in its flagship journal to that golf article, which has the amusing-in-retrospect title, “Keep Your Fingers Crossed!: How Superstition Improves Performance.” If golf is important enough to write about in the first place, it’s important enough to not want to spread misleading claims about.

2. The same issue—the Association for Psychological Science promoting low-quality publications—arises in topics more important than golf; see for example here and here.

Golf – “no big deal?” I am offended. Further, I can attest to the fact that superstition is rife in golf. In fact, if you look at the number of golf aids (physical objects, videos, magazine advice columns, etc.) that tout game improvement, it is clear that golfers are willing to pay vast amounts for such devices. Clearly they must help performance. (Sarcasm aside, I admit to succumbing to the urge for such quick fixes more often than I should)

Perhaps we can figure out how much people *really* value lucky golf items using Damisch et al! We can use a survey:

“A recent scientific study found that people using good luck charms were 33% more likely to hole their putts. How much would you value a lucky item that could improve your game by 33% just by having it in your bag?”

Along with a little demographic info and psychological profiles, we can produce Golf items that are Lucky for every slice of the income distribution! An IPO is just around the corner: GFLUK! We’ll hire a famous behavioral psychologist to lead our marketing!

Daniel: I think *this* is an idea Big Capital will back!!

It’s a uniquely human trait that we believe the dark ages pre-existed the present even as we deny that academia is presently predicated on such nefarious behaviors, indeed it’s success is generally more dependent on a kind of detachment from reality than its practitioners are willing to acknowledge and any method of improving fidelity to reality represents an existential threat.

Psychological science type research just makes for such fun and simple stories.

Can you for example imagine Dan Ariely’s “Irrational game” (https://irrationalgame.com/pages/research-reference) with solid research? It just wouldn’t be fun without Baumeister and Wansink!

Hans:

W-w-w-ait . . . is this real? This is amazing! Please tell me it’s not a parody.

I don’y have a copy (yet) but there are videos with Ariely promoting the game: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3LdgmWvh34

I suppose they could be deepfakes.

Hans:

I checked and it’s on Amazon, so I think it’s real. This is so hilarious. It’s a self-own on the scale of Marc Hauser writing a book called Evlicious . . . or Ariely writing a book called The Honest Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone—Especially Ourselves.

Maybe we need to come up with a counter-game that only includes studies that replicate. We could call it the “Dan Ariely’s Irrational” Game.

Andrew has often written to the effect that 2010 were dark ages

where people didn’t understand that it was easy to sift through data

and find bogus patterns. I learned statistics working in cryptanalysis

in the 1970s and we spent plenty of time looking for patterns in data.

We used Bayesian methods and I think completely understood these issues.

Further the methods were inherited from Bletchley Park and developed

largely by Turing. So some people understood these things not in 2010 but

not long after 1940

Nick:

As the saying goes, the future is already here—it’s just not very evenly distributed.

Lots of great applied data analysis was done before 2010—I think most of my work was pretty good, for example!—but problems with forking paths were not so well understood. I’m not saying it was a good thing that bad data analysis was done in 2010, and I’m not saying they couldn’t’ve done better; I’m just saying that their mistakes were understandable given the context in which they were working.

In any case, there’s zero excuse for the Association for Psychological Science to be promoting this crap in the year 2021.

“problems with forking paths were not so well understood.”

Perhaps, but obtaining a ridiculous result should be an extremely large and glaring clue that something’s not right, rather than an excuse to shout from the rooftops about amazing discoveries.

Also it seems unsurprising that the emergence of piles of garbage research would occur in a set of disciplines in which even the slightest questioning of irreplicable, unlikely and nonsensical results is frowned on.

It is the same in cancer research:

https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2021/12/18/estimates-of-false-positive-rates-in-various-scientific-fields/#comment-2038084

The nature of the data is more detached from everyday experience so it seems more plausible at first glance.

Jim:

My hypothesis for why psychology has all these crappy claims that stay around even after failed replication is that this sort of research does not have active opposition.

It is interesting to see from that thread that, nearly 5 years later, the early reports about cancer research have essentially ended up the same:

I would say there is active opposition to the (admittedly small) opposition. In 2012, I submitted a commentary to Psychological Sciences on the Damish et al. (2010) paper when I realized the results seemed “too good to be true”. The editor rejected the commentary based on the feedback from “a very disitnguished professor of experimental design and statistical methods” who wrote (among other things), “I would not be at all surprised if there is publication bias involved. If I had run a study on superstition and the results were null, I would not likely submit it for publication.”

I had not noticed at the time, but I later realized that the means reported in Experiment 4 of the Damish et al. paper fail a GRIM test. The measure of performance is the number of correctly identified words, so the sum of scores across participants of each condition must be an integer value. Damish et al. do not report their sample sizes for each of two conditions, just the total sample size (n1+n2=29). The reported mean for participants with the lucky charm (M1=45.84) and the mean for participants without their lucky charm (M2=30.56) cannot simultaneously be produced by any combination of n1 and n2 sample sizes that together add up to a total sample size of 29. For example, if n1=14, then the sum of ratings would be n1*M1=641.76, which presumably rounds up to 642 (it has to be an integer because it is a count of correctly identified words). But 642/14=45.857, which does not match the reported 45.84. Rounding down does not help either because 641/14=45.785, which does not match the reported mean. There is no way to get M1=45.84 from n1=14 participants. For other combinations of n1 and n2, you can get one of the means to make sense, but never both simultaneously.

“does not have active opposition.”

yeah, unfortunate isn’t it? IMO though it’s worse than that, lots of crappy work has active support and encouragement, both inside and (possibly mostly) outside of science.

But it’s possible there’s another factor: the overwhelming difficulty of controlling / adjusting for all the variables in the social environment leads people to just throw up their hands and join the gold rush for publication. \

Psychology is a very broad field. Various examples of ridiculously exaggerated effect sizes often used as examples on this blog usually originate in ‘couch’ or personality psychology, where anything goes.

Meanwhile, there are sub-fields such us visual perception/attention research or cog. neurosci. that are pretty heavily experiment based utilizing psychophisics methods. Usually, folks performing them are double majors in experimental psych. and math/physics. I think it’s unfair to treat all those sub-disciplines equally.

Navigator:

The problem is that the Association for Psychological Science, which is “dedicated to advancing scientific psychology” and whose first guiding principle is “Psychological science has the ability to transform society for the better and must play a central role in advancing human welfare and the public interest,” chooses to promote some of the worst work being done in the field of psychology.

There seems to be a problem of governance, or communication.

From way, way out of left field, here’s my favorite non-replicable study: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Origin_of_Consciousness_in_the_Breakdown_of_the_Bicameral_Mind

It’s a theory that seeks to explain a number of things through a literal change in the human brain – as represented in the gap, for instance, between the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Not so much non-replicable, more non-testable.

My conversations with classical scholars reveal a lack of support for the idea.