Awhile ago I was cleaning out the closet and found some old unread magazines. Good stuff. As we’ve discussed before, lots of things are better read a few years late.

Today I was reading the 18 Nov 2004 issue of the London Review of Books, which contained (among other things) the following:

– A review by Jenny Diski of a biography of Stanley Milgram. Diski appears to want to debunk:

Milgram was a whiz at devising sexy experiments, but barely interested in any theoretical basis for them. They all have the same instant attractiveness of style, and then an underlying emptiness.

Huh? Michael Jordan couldn’t hit the curveball and he was reportedly an easy mark for golf hustlers but that doesn’t diminish his greatness on the basketball court.

She also criticizes Milgram for being “no help at all” for solving international disputes. OK, fine. I haven’t solved any international disputes either. Milgram, though, . . . he conducted an imaginative experiment whose results stunned the world. And then in his afterlife he must suffer the indignity of someone writing that his findings are useless because people still haven’t absorbed them. I agree with Diski that some theory might help, but it hardly seems to be Milgram’s fault that he was ahead of his time.

– A review by Patrick Collinson of a biography of Anne Boleyn. Mildly interesting stuff, and no worse for being a few years delayed. Anne Boleyn isn’t going anywhere.

– An article by Charles Glass on U.S. in Afghanistan. Apparently it was already clear in 2004 that it wasn’t working. Too bad the policymakers weren’t reading the London Review of Books. For me, though, it’s even more instructive to see this foretold six years ago.

– A review by Wyatt Mason of a book by David Foster Wallace. Mason reviews in detail a story with a complicated caught-in-a-dream plot which the critic James Wood, writing for the New Republic, got completely wrong. Wood got a key plot point backwards and as a result misunderstands the story and blames Wallace for creating an unsympathetic character.

Again, the time lag adds an interesting twist. I was curious as to whether Wood ever acknowledged Mason’s correctly, or apologized to Wallace for misreading his story, so I Googled “james wood david foster wallace.” What turned up was a report by James Yeh of a lecture by Wood at the 92nd St. Y on Wallace after the author’s death. Discussing a later book by Wallace, Wood said, “Wallace gives you the key, overexplaining the hand, instead of actually being enigmatic, like Beckett.”

I dunno: After reading Wood’s earlier review, maybe Wallace felt he had to overexplain. Damned if you do, etc.

– A review by Hugh Pennington of some books about supermarkets that contains the arresting (to me) line:

Consumption [of chicken] in the US has increased steadily since Herbert Hoover’s promise of ‘a chicken in every pot’ in 1928; it rose a hundredfold between 1934 and 1994, from a quarter of a chicken a year to half a chicken a week.

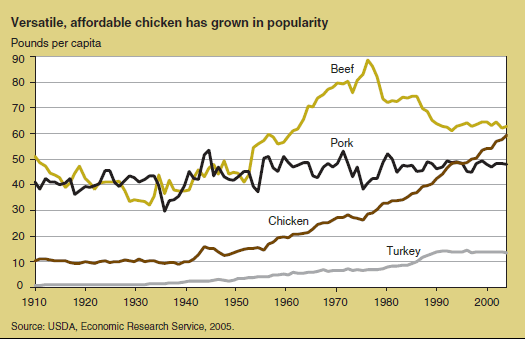

A hundredfold–that’s a lot! I thought it best to look this one up so I Googled “chicken consumption usda” and came up with this document by Jean Buzby and Hodan Farah, which contains this delightfully-titled graph:

OK, so it wasn’t a hundredfold increase, actually only sixfold. People were eating way more than a quarter of a chicken a year in 1934. And chicken consumption did not increase steadily since 1928. The curve is flat until the early 1940s.

This got me curious: who is Hugh Pennington, exactly? In that issue of the LRB, it says he “sits on committees that advise the World Food Programme and the Food Standards Agency. I guess he was just having a bad day, or maybe his assistant gave him some bad figures. Too bad they didn’t have Google back in 1994 or he could’ve looked up the numbers directly. “A hundredfold” . . . didn’t that strike him as a big number??

Well, this table http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/ers/89007/ta…

Shows a sevenfold increase from 1960 to 2004. I'm not saying you can get to a hundred, but it's not clear that per capita consumption is what went up 100 fold. You need to count population increases and exports.

In fact, look at this Table, which suggests that Pennington's estimate is too small.

http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/ers/89007/ta…

This has growth from 1934 to 2004 of a factor of 257 for chickens, and, because they were bigger chickens, almost a factor of 500 for pounds.

When something starts out near zero and becomes a nontrivial number it's easy to get confused about the "fold change". I mean it's not really that plausible that people were eating only a 1/4 of a chicken per year in 1934 but it's also hard to figure out just how off that is. After all it was the great depression, and diets were quite different then. If I told you that I am consuming a thousand times as much Suave shampoo as i was last year is that because I am spending my whole life in the shower, or because I tried a single application of my friends shampoo last year and since then it's the only shampoo I buy?

One thing I love about your blog is when you go and actually look up these innumerate claims, be it the sex of babies or chicken consumption, we all learn to not trust the "expert claims" through your example.

You could follow your own precept:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_Pennington

Nick: What's my own precept?

(The French) Henry the IVth also promised a chicken in everyone's pot every Sunday so maybe they got confused with the starting date (circa 1609).

It is good that we now have Google so that you can look up the information directly, that is to find who is Hugh Pennington, exactly.

Nick:

Yes, I agree that there's more about Hugh Pennington on the web. I thought his description in the LRB was sufficient for this purpose, though.

In any case, I emailed the contact person at the Department of Agriculture to sort out the chicken figures. Until then, I'll reserve judgment on Hugh Pennington. If it's really a sixfold increase that he described as hundredfold, that's pretty bad. But maybe I'm missing something important here.

Another way to think of it is very simple. If the average is 1/2 chicken a week, individuals who eat 1 or 2 chickens a week should be quite common. (I assume some moderately right-skewed distribution.) Any sightings?

Nick:

I eat one or two chickens a week.

I always knew you were above average.

You appear to have made Chait….um…a wee bit annoyed:

http://www.tnr.com/blog/jonathan-chait/86518/do-candidates-matter-all-yes