This post is by Phil Price, not Andrew.

I’m going to say right up front that I’m not going to give sources for everything I say here, or indeed for most of it. If you want to know where I get something, please do a web search. If you can’t find a source quickly, leave a comment and I’ll edit this post to provide one. For instance, I say below that many epidemiologists think a fairly substantial percentage of people with COVID-19 infections have no symptoms or only extremely mild symptoms, but I don’t provide a source. If you use your favorite search engine to search for, say [coronavirus asymptomatic] and you don’t see sources that agree with me, let me know. I agree it’s better to provide sources but I have work deadlines and I just don’t want to take the time. It’s bad practice but hey, this is just a blog.

Now, on to the topic of the post.

I hope we are all rooting for Sweden to find a way to limit coronavirus fatalities to a reasonable level while also maintaining their economy at a reasonable level. That would be a great thing for the Swedes, of course, but would also point a way forward for the rest of the world as we eventually try to let the economy get moving again. To me, the key distinction isn’t between voluntary restrictions on behavior (like Sweden’s) and requirements (like most of the rest of the world), but rather between whether non-essential interpersonal contact is or isn’t happening. If the Swedes are merely doing voluntarily what other countries are doing by law, the economic and social effects are going to be pretty much the same. But if they are implementing sufficient safety controls to limit the spread of the virus, and doing so in a way that permits most economic activity to continue, then we can do the same.

I do think it’s possible for a lot of business to proceed in an acceptable manner during the pandemic. I gave an example in a comment yesterday: the company that installed my HVAC system is still working, although doing many fewer jobs than usual, and they’re doing so in a way that I think is responsible. In normal times, they send a two-person crew to most jobs: a skilled HVAC professional and an assistant who schleps equipment and parts from the truck, wraps insulation, cuts metal, etc., under orders from the experienced person. But now they’re just sending one person to most jobs, even though it takes a lot longer and they now have an expensive person doing work that could be done by an inexpensive person. When they do have to send a pair of people, it’s two people who are only ever paired together, so if one of them gets sick they only put the other one at risk, they don’t rotate through the whole workforce. They ask the client to vacate the residence or at least the area of the residence where they’re working. They wear gloves and masks. Even thought they’re stretching and perhaps breaking the law on social distancing (here in the California Bay Area) by doing some nonessential work, it’s my informed judgment that what they are doing is OK.

So I can at least imagine a society in which companies shut down if they can’t provide a low-transmission work environment, but continue to work if they can do so safely, and in which people continue to see each other socially but do so in a responsible manner. I definitely, definitely would not trust the United States to be that society, at least not voluntarily, but maybe Sweden can manage it. Swedish politicians have said Sweden is special in that regard — more responsible to each other, more willing to follow government advice — and I can well believe that’s true, especially compared to the U.S. And if that’s the case, we in the U.S. can try to codify what works and make it happen here too.

Of course, there’s also the possibility that, even if Sweden is successful, that success simply can’t be replicated in the U.S. For instance, diabetes seems to increase the risk of death’ from the virus and I think we have a lot more diabetes here than in Sweden. Maybe true of other risk factors too.

And we know Swedes have been doing a lot voluntarily. According to the most recent Google Mobility Report (unfortunately from 9 days ago), person-hours at Swedish ‘retail and recreation’ sites were down 40%, transit stations about the same, and workplaces down 25%. Sweden has done a fairly substantial partial shutdown.

Is it enough?

Enough for what?

On the one hand some people say Sweden has pretty much won, they have the virus under reasonable control while maintaining a fairly healthy economy. On the other hand, they just moved into 10th place in deaths as a percentage of population, and seem on track to keep climbing the list: unless something changes they will soon take over 9th place from Switzerland, since Swiss deaths per million people only increased 40% in the past week, whereas Sweden’s doubled.

I’m going to set aside the economic question, because other than knowing Volvo is about to restart production in Sweden I know nearly nothing about Sweden’s current economic situation and I don’t have time to look into it. But I have been looking at the progress of the disease there, based on the sources I’m aware of, and…well, it’s a mixed bag.

As I mentioned in a previous post, Sweden’s death numbers show an odd pattern on Worldometers and the New York Times coronavirus stats page: they have a severe weekend undercount, which they correct later, but these sites only keep track of the latest totals, they don’t go back and adjust when they happened. That is, a coronavirus death is counted on the day it is reported rather than the day it occurred, and this seems to be a bigger issue for Sweden than for other countries. The effect happens on non-weekends too, it’s just smaller. Anyway it’s clear that on any day there is an undercount, which I suspect (not sure) may be a larger fraction in Sweden than in other countries.

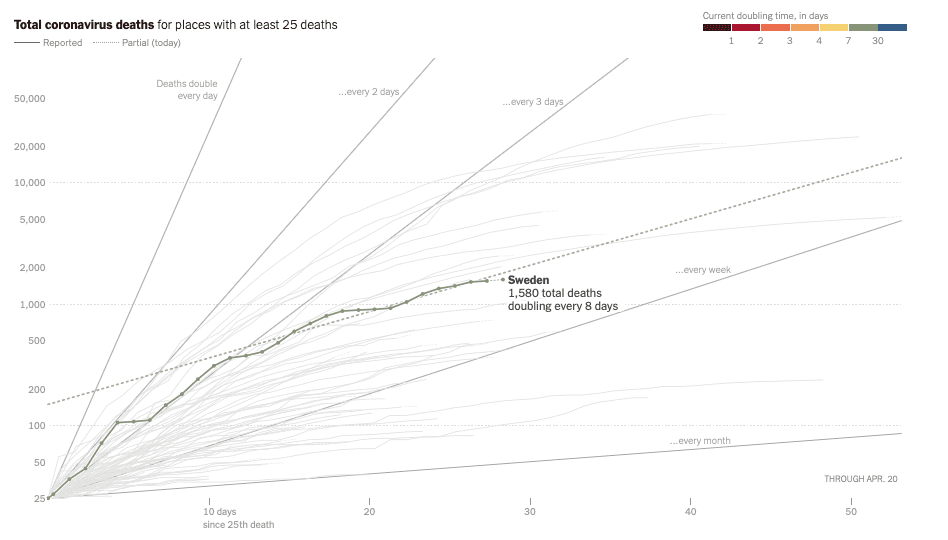

So, as of yesterday (Sunday April 19) they had at least 1580 coronavirus deaths, with deaths doubling every 8 days or so and no noticeable downward curvature on a log plot over the past two weeks. Most other countries that are at least a month past their first deaths seem to have slowed the increased the doubling time to more than 10 days, usually more than 12. And those doublings really multiply up over time: Four doublings in a month rather than three, that’s…well, that’s an additional factor of two in deaths, is what that is. Viewed through this lens, Sweden’s approach does not seem like a success. Yes, in deaths per capita they are still way under Belgium and Spain and Italy and the UK, but those are all countries that got started earlier and didn’t implement any kind of social distancing until it was too late to prevent mass casualties. Sweden, like the U.S., had time to learn from those other experiences.

So that’s the bad news.

The good news is, Sweden has not had the huge surge of cases (and subsequent deaths) that would have been expected if they weren’t taking effective measures at slowing the spread of the virus. Those voluntary measures they’re taking are definitely helping tremendously.

You know, even just writing this post has helped me put things in perspective. When I started writing I was baffled by what I saw as contradictions between claims coming from Sweden that they had been successful in controlling the virus while maintaining their economy, and the death numbers that seem to show no such thing, but now that I’ve looked at the numbers again and read a few opinion pieces again I am no longer baffled, I simply think there are different definitions of ‘success.’ Sweden avoided overwhelming their emergency health care system, as happened in Italy and Spain and New York. Maybe that’s what they mean by success. Yes, their per capita death count is still increasing faster than that of most of their peers, but not by a huge amount, and presumably they think they can bring the growth rate down soon. They might end up in the top eight or top five countries in deaths per capita — they’ll be number 9 in a few days — but that means there are several other countries that would be thrilled to be in their position just in terms of deaths per capita, and Sweden’s economy is presumably stronger too (I assume. As I said, I know nearly nothing about their economy). If avoiding the fate of Belgium and Spain and Italy is ‘success’ then Sweden is a success. To me that seems like an awfully low bar, but different people have different values and I’m sure lots of people would agree that that makes their approach a success.

Funny, by thinking about this post as I was writing it I have rendered it uninteresting to me. But what the hell, I’ll post it anyway, at this point the effort is all sunk cost.

This post is by Phil.

It sounds like whatever happened in Sweden (voluntary measures? luck or happenstance?) they’ve done what the USA media campaign claimed as the reason behind shutting things down. Maybe they are seriously fudging the reporting of deaths (more than ‘most anywhere else?) but another hypothesis would be that Sweden is simply a country where a crashed health-care system was unlikely to happen in the first place.

Just here in USA we have places which did roughly similar timing and intensity of shutdown to New York but which experienced something more like Sweden than New York in terms of “flattening the curve”. We even have places where less shutdown was done later (relative to New York) but the health care system was stressed only by the shutdown rather than a non-existent influx of COVID-19 cases.

So I’ll pitch my currently favored hypothesis. There are factors that cause a Lombardy or NYC level of health care system overload which are far more important than where on the spectrum of shutdown timing/intensity that region falls.

Under the counterfactual that New York City had moved two weeks earlier and somewhat more aggressively into shutdown than they actually did, I find it completely plausible that they might well have massively overwhelmed their inpatient/ICU/ventilator resources.

Under the counterfactual that some of the early-shutdown areas of California or Europe had waited another 2-3 weeks and been less thorough in shutting down, it is possible their health care systems might have survived without collapsing.

I think once real science starts being done to understand both the epidemiological and public policy aspects of this experience, it will be possible in retrospect to deduce other factors which trump the exact timing of a shutdown. And I am not talking about sticking heads in the sand and pretending their is no pandemic. I mean doing a Sweden type approach versus a San Francisco one as the possible range of responses worth studying.

The key to how high the infections go is how quickly social distancing was started relative to say the Nth community infection where N is a small fixed number. Let’s call it 20.

So, to tell us whether NYC vs say LA county were later or earlier, or more or less effective, and how much, you have to tell us the date they shutdown, the effectiveness of the shutdown, and the date they had 20 community infections (not ascertained cases, infections).

So, all anyone has to do is just figure out magically when the 20th community infection was… So it turns out that this is a really hard problem, and requires a fairly complicated bayesian model of the dynamics and of the testing, and of the effect of mitigation on the spread rate and soforth.

Without a detailed model that we can do inference from, the best guess we can do is say that if the early spread rate was similar in two places, then whoever got to a higher peak per day rate acted later.

So since NYC and LA had similar early spread rates in the cases, basically the evidence says LA acted earlier and that’s 100% why they have a dramatically lower peak than NYC.

Daniel,

I think the evidence is at best suggestive that the most important difference was timing of the shutdown. Making statements like “100% why…” in the absence of any reliable data on determinants, much less a well thought out model to incorporate that data, is just silly.

You have what we might call a “cognitive prior” that says “100% why…” by which I mean that’s what you believe and will continue to believe absent any overwhelming evidence otherwise. Given the paucity of evidence in this situation, if you want to stake out such an absolutist “prior” position there’s not much anyone can do to convince you out of it.

You seem to be pretty good at pushing back against every mathematical model that gives a conclusion that isn’t whatever your favorite conclusion is.

So far however you have had ZERO history of providing quantitative estimates of anything, except that you estimated a counterfactual that if we just reopened the economy we’d have about 20,000-50,000 more deaths and the whole epidemic would be over.

https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2020/04/18/the-evidence-and-tradeoffs-for-a-stay-at-home-pandemic-response-a-multidisciplinary-review-examining-the-medical-psychological-economic-and-political-impact-of-stay-at-home-implementation/#comment-1304891

So, please. Show us the calculations. I’d like to hear your model for what’s going on.

I don’t have a model and neither do you. You make up numbers that illustrate your own off-the-top-of-your-head guesses about the situation (which is usually something pretty dire). I make up numbers to illustrate my off-the-top-of-my-head guesses about the situation (usually something along the lines of “second worse respiratory virus EVER”).

The “calculations” you like to show are all Drake Equation type stuff where you multiply together a long string of guesses and assumptions and present the product as if it were somehow descriptive of reality. I’m not really interested in that sort of thing.

Here I try to spell it out: https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2020/04/20/coronavirus-in-sweden-whats-the-story/#comment-1310171

> that’s 100% why

The basic reproduction number is surely higher in NYC than in LA. Also, it seems that there were more independent introductions in NYC than in LA.

Sure, I can see that I should be more explicit. In reality, the growth rate in terms of per-day is irrelevant. All exponential growths at constant rate are equivalent when you express them in terms of a dimensionless time.

In the dimensionless analysis, all epidemic curves can be considered the same in the intermediate asymptotics between the early stages where the actual individual counts matter (ie. the new introductions, whether there were 30 or 31 cases etc), and the late stages when it stops being exponential. All we care about to understand the mitigation is this intermediate stage because all the action was in that intermediate stage. In the intermediate stage you can write:

Infections(t) = 20*exp(t)

where t is measured in e-folding times since the “apparent 20th case”. In other words t = (date – date0)/efoldingtime

t=0 is just the time such that as t grows in the region more than say 5, infections(t) approached the correct curve.

What it means to say that one place acted earlier than another then is just that their dimensionless time at the point where they took sufficient mitigation to dramatically alter the growth rate was at a smaller value for t.

that’s why it’s 100% t that matters, because as long as the growth was exponential with some rate, there’s a symmetry that makes everything else go away.

If you’re “lucky” in your region of the world, the efolding time is large so that you have many days to get to the same t and so can deliberate longer about the best plan. In both LA and NYC the efolding time was small, somewhere in the range of doubling every 2 to doubling every 4 days, which is efolding time of 3.6 to 5.8 days.

You said that “the best guess we can do is say that if the early spread rate was similar in two places“ but I think a better guess is that it was spreading faster in NY than in LA. You seem to argue that it’s irrelevant but I think we can agree that it’s easier to act “early” when that dimensionless time is flowing more slowly. The progression of the disease happens in standard time so when you observe 10 deaths or whatever it’s already “later” if the reproduction number is higher. It’s also easier to detect the first N locally transmitted cases and act “early” if those cases appear in a few clusters rather than several, by the way (you ignored that point).

Post-action the growth will no longer be exponential when the reproduction number is under control but those numbers will follow different paths in different places so the evolution of the system and the peaks will be different. You may want to reparametrize the time to force some symmetry but the progression of the disease and many other things relevant for the outcome happen in standard time and are not invariant under those reparametrizations.

> I think we can agree that it’s easier to act “early” when that dimensionless time is flowing more slowly.

Yes, I did actually explicitly say that, but the timescale was different between the two by the difference between 4 vs 6 days or something. Furthermore Wuhan and Italy gave us plenty of warning as to what would happen. In days, we had plenty of days to take action, yet we didn’t. This is why the news is full of exposes on what Trump knew and the news media keeps asking him why we did nothing in Feb.

>Post-action the growth will no longer be exponential when the reproduction number is under control but those numbers will follow different paths in different places so the evolution of the system and the peaks will be different

True, but the peak of cases in the hospitals etc occurs because of a backlog of cases that accrued in the exponential phase. We observe and hospitalize cases say 10 days after they’re created, which is ~ 2 dimensionless time steps.

To get a feel for the numbers, if dimensionless time is on the order of 5 days. Then there have only been 13.8 dimensionless time steps since Wuhan lockdown on Feb 11 and since there’s a ~10 day delay from infection to seeking care, and that’s 2 dimensionless time steps, we’ve had basically ~10 dimensionless time steps from the lockdown in wuhan to when the cases we’re seeing NOW were created.

LA cases per day started being constant April 1 or so. That’s when we saw the effect of Mar 19 shutdowns… so 13 days?

The big point is that once you knew an exponential growth was underway, you had *one* parameter to deal with: “how early in dimensionless time will you put in mitigation that drops the growth to subexponential?”

Anyone who knows anything about epidemics, and wasn’t playing political bullshit, would have and DID tell people: shut everything now.

This was hardly the first of its kind on Mar 10:

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/coronavirus-cancel-everything/607675/

if NYC had shut everything Mar 10, it would have been ~ (22-10)/5 dimensionless time steps earlier, and the hospital cases would have been basically 11 times smaller.

The hospital surge was entirely dependent on that one parameter: how many dimensionless timesteps did the region wait from the “nominal 20th case day” until they put in stay at home type orders?

I google it and see that it was Mar 22 in NYC and Mar 19 in CA. However local schools closed in CA on Mar 13, and other schools in CA were already closing first week of Mar. Many of the big employers were doing “work from home” first week of Mar. There were thousands of cases in Italy first week of March. We knew what was coming, and in that time period we had a unidimensional decision: what day to close everything. And it was always going to be worse the longer we waited. And all the articles arguing about how things worked in 1918 said the same thing… earlier was always better.

That’s EXACTLY what S Korea did, it’s what Taiwan did, it’s what Singapore did, they all got control as fast as possible in dimensionless time. And, because they devoted resources to test and trace, they also were able to get through their bolus of patients and do useful things earlier.

If you’re happy with your model that you explains 100% of the difference between NY and LA with a single parameter based on the point in the exponential phase where some non-specified mitigation action happens more power to you. This kind of universality reminds me of the IHME model that tries to fit all the curves into a common pattern but Italy has already failed to replicate the path of Wuhan. Italy is not Wuhan. NY is not LA. Adjusting one or two parameters may not be enough to account for the differences.

Carlos. Beyond the onset of mitigation of course the model is insufficient. But this model was sufficient for me on Mar 22 to make a public prediction (to my FB friends) that we would have the evidence to know for sure if we had flattened the curve in CA by April 12.

Which was in fact https://www.latimes.com/projects/california-coronavirus-cases-tracking-outbreak/

about 4 or 5 days past the peak of the 7 day moving average that LA times plots in terms of new cases. Now we are in more or less stasis with linear growth at 1200 a day for the last 10 days or so. I expect over the next 10 days further declines because it seems that CA is doing a pretty good job of at-home isolation but I have no magic crystal ball that extends outside the asymptotically valid intermediate range.

I freely admit there is no such symmetry trick I can do to simplify the problem down to picking a single number to predict how well we will do in the future. That requires actual epidemiology and knowledge of how well different policies will work. But during that phase, exponential growth unmitigated, all curves collapse to a single curve with the appropriate analysis.

Intermediate asymptotics are a super-valuable tool, anyone who wants to know more about them should read “Scaling” By G.I Barenblatt but the applicability is limited.

Today, we have a much harder problem. And we need leadership and epidemiological investigations. We need ways to measure, test, trace, track the stats, estimate whether growth is occurring, estimate prevalence, and of course figure out treatments and drugs and etc.

Do it. Model what you think happened. As I mess with mine I am seeing more and more that the number of actual cases had already peaked when the first US death was reported. Eg, the high variance in cases/deaths reported early on is only reproduced by the model if that is the case:

https://i.ibb.co/zsJ1L7t/apr20.png

https://i.ibb.co/RPxQYV6/sirresults.png

That isn’t a feature I expected to explain at all. Of course we can make the testing strategy more complicated to reproduce it too. As I keep improving it hopefully we can get a prediction out of it.

loool, ‘as I mess with mine’. That’s rich.

Daniel, I understand what you are saying. You model comparative infection growth by country using the date of the first N community infections (I’ve seen N = 10 used) as the starting point for tracking the hoped for S-shaped curve as the epidemic progresses day by day. AND you also do a per capita comparison of confirmed cases or fatalities, to adjust for different size populations for each country. Yet an earlier shutdown isn’t enough, certainly not an absolutist “100% why…”, LA had a dramatically lower peak than NYC.

I agree with Brent Hutto, that prompt measures for limiting virus spread and preventing healthcare system overload is important but by no means the only or even major determinant. This is epidemiology not just statistics. Unknown factors resulted in fewer confirmed cases, fewer deaths, and only mildly impacted healthcare systems in urban areas of Michigan, Georgia, and Louisiana than in New York City. Ambient temperature wasn’t the reason, because Michigan is cold unlike Georgia and Louisiana. Yet despite:

-much more poverty

-disproportionately adversely impacted populations

-imposing shutdowns later, and

-significantly less well-resourced medical facilities,

Detroit, New Orleans, and Atlanta have gotten control over and reduced numbers of COVID hospital patient admissions and deaths by 50% to 90% as of today.

Yes, California shut down before New York City, but its large urban areas such as San Francisco and Los Angeles are arguably more susceptible to a human to human transmitted disease (due to worse sanitary conditions, more homelessness, and the nation’s highest poverty levels) than New York City. There are additional confounding influences, such as the impact of New York City’s subway system, that can only be accommodated by an adequately detailed model. (There are no subways nor other public transportation in California.) This non-peer reviewed working paper The Subways Seeded the Massive Coronavirus Epidemic in New York City (JE Harris, MIT via NBER, 16 April 2020) is getting a lot interest. Other US cities have subway systems, but none as old and extensive as New York City.

Ellie:

According to this analysis by Alon Levy (“That MIT Study About the Subway Causing COVID Spread is Crap”, you shouldn’t blame the subway.

If subways aren’t a danger, then we need to rethink things. If crowding dozens of people together in close proximity is not a problem, then what *is* dangerous (besides a hospital full of sick people and extreme examples like that)? If subways are not a danger, then there must be a huge number of other things that are not a problem and we should identify them.

Or is the paper just bad, so: Paper = Bad .AND. Subway = Bad.

Living in Tokyo (with it’s massive dependence on (it’s amazing) public transportation system), I was convinced Tokyo was going to be an instant, incredible disaster. It hasn’t been. So far. New cases per day went up to 200 or so, and are now down to 100 or so (for the last two days) for a population of 13.7 million.

I went to jazz gig at a bar on March 19th, expecting the bar and trains to be empty on a Thursday. They weren’t. Coming home, the trains were crowded, the locals around me all quite inebriated. (Oops: Friday was a national holiday.) I thought I was going to die.

I’m still here. Go figure.

Four flaky theories. (1) Maybe masks really do help on the subways. (2) Maybe everyone really is washing their hands. (I am.) (3) The Japanese take their shoes off in their doorways, so they don’t track the virus inside. (4) Maybe the Japanese are just cleaner than Americans. (In my college days, I grew my hair long and shampooed it every morning, and a Japanese art history PhD candidate friend told me “You’re the cleanest non-Japanese I’ve ever met”.)

FWIW, the tube here this morning was discussing a cluster of cases from a karaoke party. Confined quarters, extended period, everyone breathing on the table, virus accumulating on said table, people touching said table, and touching their faces. One of the attendees had been in “close intimate contact with one infected person”.

To quote a friend who is a nurse at MGH: “We’re all going to die.”

Curiouser and curiouser. Every day, I know less about this thing.

It’s possible to agree that the MIT study is crap while still believing transmission risk is high in a crowded subway car. If you’ve got someone standing three feet from you, coughing coronavirus at you, that’s gotta be risky.

I wouldn’t think it would be controversial to say that the number of different people an infected person interacts with closely each day — ‘interact with’ meaning you spend at least twenty seconds within a few feet of them, or else you touch something they recently touched — is likely to be causally related to the risk of passing on the disease. If I were betting this is definitely the way I’d bet.

Of course, as others on this thread have pointed out, there are other factors too: what are household sizes, to what extent to old and young people share housing, what messages were people getting from politicians and other newsmakers, yada yada. But it’s hard for me to imagine the subway isn’t a factor.

Hello Andrew,

I just read it. I also read the 90 some comments, including one by the author of the NBER paper, physician Jeff Harris, who is a professor at MIT. Note that Alon Levy is a writer whose hobby and occupation is urbanism, having started his career studying math, according to the his bio.

Ad hominem aside, I will point out that Jeff Harris said (Disqus links don’t work well; try this http://disq.us/p/28p6keo or this https://nyc.streetsblog.org/2020/04/17/that-mit-study-about-the-subway-causing-covid-spread-is-crap/#comment-4879590864 for all of it)

Let’s see what other responses Harris has to Levy.

I’m just going to nod knowingly and pretend that I am following all this, while hoping someone figures all this out and comes back and tells us what is going on. Ellie, it sounds like you are volunteering to look into this further [he said nodding knowingly].

Yes, Terry. I volunteer. And I am here now to report my findings to you. Actually, I thought it would be clear after reading the quoted section but I truly did need to read the article that Andrew linked to first, to understand. I’m sorry about the ambiguity.

People who spend eight hours a day working in the New York City subway system are contracting COVID-19 at a three times higher rate than people who don’t. That’s why it might not be a good idea for the subway to remain open for the general public right now.

At the very least, it might make sense to shut the subway for a week like some New York City councilmen are asking Cuomo to do, in order to give it a deep cleaning. Reopen it after that and see if it helps.

Ellie:

I see, I see. That’s what *I* was thinking [he said nodding knowingly].

Ellie:

So is Harris right? Does his paper show this? To put it another way, is the Harris paper (A) crap, or (B) the opposite of crap?

Ellie, It does seem like many of the hot spots in the Levy article are where the NYC subway lines terminate. Which, assuming most essential employees enter these points to commute to the city interior? Yes, no, maybe?

Terry, Phil, Ellie:

Good points!

I warned about this on here like a month ago. It was obvious NYC was going to get hit hard like Italy and Iran due to that smiling robot: https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2020/03/07/coronavirus-age-specific-fatality-ratio-estimated-using-stan/#comment-1259326

Ellie: All those things you mention just change the time scale… You can ask “why is the time scale different from one place to another” but once you know that the growth is exponential… it’s all about “how many e-folding times have you waited”

So what *date* you put in your mitigation is not as important as *how many e-folding times did that date give your epidemic to grow*

Ellie, note that I’m not trying to minimize the role of Epidemiological investigations… WHY is the e-folding time different in different places in terms of physical aspects of the environment is very important in the long term to understand how to MANAGE the epidemic.

But in the early stages, the e-folding time in a given region isn’t under our control. it just is what it is and it depends on people’s mobility and the number of contacts per day and family sizes and school dynamics etc. In fact, I *define* early stages as the time past 20 or so cases and *until* we do mitigation that makes the e-folding time non-constant in time.

Before that point, our only control variable is *when* do we pull the trigger on starting the dramatic mitigation that changes the e-folding time.

“(There are no subways nor other public transportation in California.)”

You can tell that someone’s never been to San Francisco when they claim that BART (definitely a subway) and MUNI (mostly surface but underground and following the BART tunnels in downtown SF) don’t exist. CalTrain carries heavy traffic in and out of the city daily. And, of course, there’s an extensive bus system and limited trolley system. BART and MUNI alone carry close to 600,000 passengers per workday.

And San Francisco’s poverty level is lower than NY City’s, too.

Now, homelessness is a real problem …

Ha, I had missed that claim that there are no subways or other public transportation in California. That’s hilarious. WTF.

dhogaza and Phil,

Please no wtf at me. I lived and worked in Palo Alto for four years, got a graduate degree from Stanford. I took CalTrain many times, as well as BART and the trolleys and buses in San Francisco. There is still nothing comparable there to New York City’s subway. BART is below ground in places as are the trolleys, but not comparable to SF.

There is nothing in Los Angeles that even comes close to the New York subway system. Play nice.

Also, it is kind of irrelevant, because regardless of how little or much one likens the SF mass transit system to New York City’s, the fact remains that COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths are less than that of New York City by at least an order of magnitude. There is clearly something different going on between SF and NYC.

Oops, sorry typo:

>BART is below ground in places as are the trolleys, but not comparable to SF

should be

BART is below ground in places as are the trolleys, but not neither are comparable to the underground transit system in New York City.

Aren’t you forgetting some of the, in my opinion, biggest differences between LA and NYC:

1. LA is spread out over a wider area meaning you meet fewer people on a normal day in LA than NYC

2. More people use public transport in NYC than LA and The NYC commuters come from a wider socioeconomical background

This results in average newyorkers comming into contact with more people and those people are from a wider background.

> So I’ll pitch my currently favored hypothesis. There are factors that cause a Lombardy or NYC level of health care system overload which are far more important than where on the spectrum of shutdown timing/intensity that region falls.

> Under the counterfactual that New York City had moved two weeks earlier and somewhat more aggressively

> Under the counterfactual that some of the early-shutdown areas of California or Europe had waited another 2-3 weeks and been less thorough

Why are these counterfactuals the ones to think about if the question is to try to think about factors other than shutdown timing/intensity on healthcare system outcomes?

My points being two:

1) There may be some places (perhaps NYC) where it literally was not possible act soon enough to avoid an overwhelmed hospital system

2) There may on the other hand be places where no matter how much “too late” they shut down, the hospital system would not have been overwhelmed.

I’m saying depending on some as yet unknown/unstudied important, major factors the ability of “social distancing” policy to determine the course of events may be insufficient to change the outcome.

Hey, thanks, Phil Dude!

Not sure what you’re thanking me for, but you’re welcome!

> Those voluntary measures they’re taking are definitely helping tremendously.

I guess the obligatory measures (like gatherings of more than 50 people being banned and bars being table service only) have contributed as well.

Discussion on these blog comments seems to continually feature an expressed or implied attitude that someone, somewhere is arguing in favor of doing absolutely not one blessed thing in response to a major public health emergency. As far as I can tell that is a strawman. As I mentioned in my comment above, surely at this point the range of possible policy options we need to discuss does not include ignoring the virus altogether and packing 50,000 people into soccer stadiums or anything of that ilk.

From what I’ve read, Sweden was fairly timely in making mandatory the obvious measures that nobody in his right mind would argue against. The difference in “The Swedish Experiment” is stopping there and making everything else suggested, optional or voluntary.

It’s kind of odd (to me at least) that a society often thought of as the stereotypical social democracy has more faith in the judgement of its individual citizens than places which like to style themselves exemplars of robust individualism.

Believe it or not, some people are opposed to the closing of nightclubs and the cancellation of parties, concerts, sports events, religious gatherings and whatnot. Anyway, I was just pointing out that there were also restrictions imposed by law in Sweden. That’s all.

Carlos, sorry. I guess I shouldn’t have said “nobody” was proposing that stuff. I keep losing track of the world we actually live in, full as it is of numbskulls and arrested development cases. Sigh.

> Discussion on these blog comments seems to continually feature an expressed or implied attitude that someone, somewhere is arguing in favor of doing absolutely not one blessed thing in response to a major public health emergency. As far as I can tell that is a strawman.

Then you are not looking very hard.

Effectively in the case of Sweden we have a temporal autocorrelation issue, leading to a much smaller effective sample size if we were trying to estimate their pandemic curve.

Also I recommend articles on how good Sweden is be written on Wednesdays, not Mondays.

> Wednesdays, not Mondays.

This is true but almost funny.

Its hard for people not to see rainbows when they are in dire situations (e.g. early reports of effective treatments and recently a biased analysis that suggest ACE markedly decreases mortality. Never digest science before it has been adequately aged).

The Swedish death rates are updated daily by the Swedish Department of Public Health (Folkhälsomyndigheten) with the actual dates of death. The dates are not corrected in the Johns Hopkins or Worldometer or wherever they track daily deaths, only at the department’s website. It makes quite a difference to the curve, since most reported deaths happened many days or even weeks earlier. We are now seeing a plateau.

You can check it out at https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/09f821667ce64bf7be6f9f87457ed9aa

I don’t know if there’s an English version but if you’re looking for deaths, the word in Swedish is “Avlidna”. “Åldersgrupp” means “age group” and “dag” means “day”.

How deaths are reported is also important. What systems are being used? How is it organized? What is being fed into that system? Is that same system used by everybody? Someone called Sweden a “statistical powerhouse” in an article and that is an apt description. In the this case, the Swedish personal ID number is an important factor. Every Swede is given a personal ID number at birth (or at permanent residence) and that number is used in every interaction with institutions like health care, banks, libraries, for employment, memberships in organizations, everything. All reporting is centralized, the same systems used by all entities private or public. This means Sweden can know and verify deaths faster and more accurately than probably any other country. (If you can find a country that’s actually faster I’d like to know how that is organized) It is impossible to get “lost” in Sweden. You will not find bodies hidden and stacked in nursing homes like what has happened in Spain and the US. This also makes a difference. The weekend lag is real, but all other countries and states also lag – and not by a day or two. Why the weekend lag is more pronounced in Sweden is probably related to this.

Thanks, it is hard to know what are real differences and what are artifacts.

In Canada we have had 1,758 compared to Sweden’s 1,765, but we have almost 4 times Sweden’s population. With universal heath care, a health care system currently with some extra ICU space and most of our deaths in nursing homes, I don’t believe there is that long of a delay in reporting deaths…

And of course, differences in demographics – Demographic science aids in understanding the spread and fatality rates of COVID-19 https://www.pnas.org/content/early/2020/04/15/2004911117#sec-1

Looking at Worldometer.

I was comparing identified cases per million to numbers of tests per million. Obviously, those two metrics should be viewed in relationship to each other. Sweden ranks lower, relative to other countries like Switzerland, in the ratio of number of tests to identified cases. That’s not a particularly good sign.

Sweden only does strategic testing. Which means they only test people who need hospital care and health care workers showing symptoms. They test only when a positive test would change something. If you have symptoms but you don’t work in health care and you don’t need hospital care, the rule is you stay home and isolate. A test would then change nothing. A negative result could even be detrimental, as it could give a false sense of security, when you could get infected the next day.

Instead, Sweden does random testing particularly in Stockholm (where the outbreak is) to get an idea of how many are infected at a certain time.

If there was an infinite test capacity, maybe you could choose a different strategy, but I think having some system is necessary.

Ani –

Thanks for the information.

> They test only when a positive test would change something. If you have symptoms but you don’t work in health care and you don’t need hospital care, the rule is you stay home and isolate.

FWIW, I would guess that “compliance” with such a directive, and the ability of people to follow such a directive (given the levels of social support) in Sweden is higher than in the US.

> Instead, Sweden does random testing particularly in Stockholm (where the outbreak is) to get an idea of how many are infected at a certain time.

Yah. That seems to me like a very good metric for assessing the degree to which a government should mandate social distancing – but it doesn’t have to happen mutually exclusive with testing people with symptoms.

> If there was an infinite test capacity, maybe you could choose a different strategy, but I think having some system is necessary.

Something must be up with my keyboard as posts keep going up before I’ve hit the “submit” key…

…

Anyway:

> If there was an infinite test capacity, maybe you could choose a different strategy, but I think having some system is necessary.

I completely agree. But the underlying question there is why isn’t our capacity greater. IMO, increasing capacity should be a priority. Another question is whether some complacency can develop to the extent that people start of focus resources and energy on a policy of limited testing.

Please beware of drawing conclusions about miltivariant causality by comparing a singular variable.

Sweden is vastly different from the US, and in particular certain parts of the US, along a long list of attributes. Yes, like prevalence of diabetes, but also issues like population density, number of average people living in a household, access to healthcare, etc. They even differ greatly along important metrics from more similar countries like Switzerland, such as in proximiy and degree of travel to/from an “epi-center” like Lombardy.

I think it makes little sense to compare the impact of social distancing policies across countries unless you do a whole lot of work to control for potentially explanatory variables. Especially when the quality of data, at least at this point, are so poorly validated, so variable across context, so quickly evolving, so much just a singular point in time, More than likely, such exercises based on cross-sectional data, without the power of longitudinal analysis, serve better to confirm biases than anything else.

Multivariate…

That’s why my default position is, show me what really determines where the health care system is going to crash and where it is not. How do you distinguish New York City and Detroit from Stockholm and Dallas? Then once we understand that we’re ready to ask questions about social distancing.

Sorry to intrude this beatuful discussion but can’t constrain myself. Apropriate term is acually phisical distancing.

That’s as may be but I have yet to hear the phrase “physical distancing” uttered even once while the phrase “social distance” has occurred in (my rough estimate) 99% of conversations I’ve had with anyone over the past month.

‘Social distancing’ is an oxymoron, just like ‘alone together’.

How is distance sociable?

Actually, in terms of proximity to the Lombardy epicenter, the Stockholm outbreak (which has more than 75% of cases and deaths in Sweden) started when thousands of people came home from spring break skiing in Italy late February. They tried testing and tracking all of them and did fairly well, but testing capacity was low at that time and community spread was soon a reality. Mitigation strategies were then implemented, social distancing, closing of universities, working from home etc. Intensive care capacity was more than doubled and so far 20% of icu beds have not been used.

The plurality of deaths in Sweden are people 80 years and older, many 90 years and older, who got the virus in nursing homes and died there. Most seniors in Sweden receive help, care and service in their own homes and do not move into nursing homes until they are very sick and fragile, so fragile that on on average they die within months of moving into one of these homes. Those homes are like little live-in hospitals, and if the virus gets into a place like that, a lot of people can get infected before it’s discovered. Social distancing, voluntary or not, is not possible since they require 24/7 care from nursing staff coming and going in shifts.

These seniors are too fragile to endure or survive intensive care (intubation, for example, is likely to cause only suffering with little result). They are thus are given care by the doctors and nurses at the nursing home and are only moved to intensive care units if the physician think the patient would have a chance of surviving it. Sweden is now rethinking not their mitigation strategy as a whole, but the nursing homes – their size, the way they are staffed, how the rules and incentives for privately run nursing homes are working. The coronavirus has exposed some serious flaws in the capacity of the current system to protect the most vulnerable elderly and this is what is being discussed in Sweden today. Not the mitigation strategy, which has broad popular support and is followed by most people, most of the time.

It’s hard to know how many of those seniors would have died within the next few months anyway, but Sweden is tracking the overall mortality and comparing it to the average of previous years.

Thanks for the info.

Thanks, Ani.

I wish all-cause mortality numbers were easier to find and were more frequently updated. I would be as interested in those as I am in deaths attributed to COVID-19.

Old people everywhere are way more vulnerable to the virus. About 15% of Sweden’s reported coronavirus deaths are under 70, and 5% are under age 50, I think those are not atypical of other countries. I also wish data on life-years lost were routinely available, rather than just ‘deaths’, but I haven’t seen a compilation of such data.

I recently read an article that quoted Swedish nursing home attendants who were dismayed and angry about the lack of support they’ve been getting. No protective gear, no disinfectant. One of them said they know there are asymptomatic people, they know some of the nursing home staff must have the virus and must be infecting the residents, but they are given no way to protect them. (I was going to mention this in the post, but forgot). This seems odd because the resources that would have to be made available are so small.

My worry about Sweden is similar to my worry about California (where we did a relatively early shutdown): the number of deaths so far is relatively low and we are nowhere near exhausting the capacity of our hospitals, but the number of deaths has been growing exponentially for the past two weeks with a roughly constant exponent. The growth rate is similar to Sweden’s, a doubling every 8 days or so. Sure, it’s not the doubling-every-3-days that we’ve seen in some other places, but still, if we don’t bend this curve further at some point then things will eventually get bad. Those remaining 30% of hospital beds can fill up in a hurry. (And of course, to the people who are dying and their families it is already bad). The lack of further progress, day after day, is disturbing. I’m aware that deaths is a lagging indicator of infections, and in both California and Sweden there’s reason to believe or at least to hope that infections are slowing, but neither place has done sufficient testing to be sure. It just seems way too early for a victory lap. When there’s a week with fewer deaths than the previous week, that’s when I’ll breathe a sigh of relief.

Absent an effective vaccine and/or widespread screening, testing, tracing and segregation of newly infected persons just about everyone is going to eventually be infected with this virus. And a large proportion of the oldest and most vulnerable people who get it are going to die.

So starting early or being more hardcore with the shutdown is literally to spread out the inevitable. Not to avoid the inexorable spread of the virus throughout the population. That will only happen through immunity (herd or vaccine) or an extremely difficult and expensive to implement classical Public Health approach.

P.S. I say “extremely difficult and expensive to implement” because of COVID-19’s particular combination of ease of transmission, largely asymptomatic presentation and long period of shedding virus. It makes half-measures of testing and tracing nearly useless IMO.

I have my doubts about a vaccine since there has never been a safe and effective coronavirus vaccine. But why do you assume a large proportion of the most vulnerable need to die? Most of the deaths seem to be due to aggressive use of high pressure ventillation which is dropping out of favor and hyperbaric oxygen therapy is reported to improve all the strange symptoms. Combine that with fixing the vitamin c deficiency that undoubtedly exists (I guess this hasn’t been measured because people are worried about contaminating the HPLC machines) and you can easily reduce mortality by 10-100x.

Also, spreading out the inevitable may be worse than you think. If antibodies wane after a year or so in the 80-90% of mild cases (like for some other coronaviruses) flattening the curve pretty much guarantees the virus becomes endemic vs burning itself out.

Given what little I know about vaccine efforts for other coronaviruses, plus the history of influenza vaccines, I would be very surprised if a highly effective COVID-19 vaccine will be available any time in the next year or two. Never is a long time and something may eventually be found but it is highly unlikely to come in a meaningful time frame for dealing with the ongoing spread of the virus.

I sincerely and devoutly hope to be proved wrong on that.

And it very well could be that a few puffs on a cigarette fix the loss of spontaneous (non-intentional) breathing like reported for mountain climbers and the Tour de France cyclists when they climbed into the alps.

But we know that it’s better if everyone dies and western civilization is destroyed than to ever recommend that treatment.

New smoking data out of France: https://www.qeios.com/read/article/574

Phil, CA has not been growing exponentially. New cases are growing linearly at a constant ~1200 per day for the last ~20 days.

https://www.latimes.com/projects/california-coronavirus-cases-tracking-outbreak/

Sweden on the other hand is still in exponential phase as far as I can tell so far

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/daily-cases-covid-19?time=..&country=SWE

But they are much earlier in the curve, at only 500 per day and they are doubling every ~ 8 days. If they continue like that they will be at CA levels next week, and at NY levels of 10000 cases per day in log(10000/500)/log(2)*8 = 34 days

So again it all comes down to when they will get out of exponential phase… People don’t seem to get exponential growth. It eats everything. If you are in exponential growth with COVID you have ONE goal… End the exponential growth . That’s it.

Sweden will end the exponential growth, the question is just how costly will their math lesson be.

Sweden had the highest reported cases per day 2 weeks ago according to that. Doesnt look like exponential growth to me.

Hmm… strange that this morning when I pulled up that graph it looked VERY different from the way it does several hours later… :-(

Not sure if maybe I got some kind of cached version, or something else… but I agree with you now that they’ve been flat with a lot of wiggles for ~ 2 weeks.

Perhaps I’m overly skeptical of looking at ‘cases’. A few weeks ago it was pretty useless: it was very context-sensitive, and in places like New York and northern Italy that were overwhelmed by hospital patients and underequipped for testing it was clear that lots of serious infections were not recorded as cases; at the same time, from all-cause mortality it was clear that this was also true in many other countries too, even those that weren’t overwhelmed. So I’ve only been looking at deaths, well aware that they lag infections by a month or so. Sweden and California are both growing exponentially in deaths.

But for countries that aren’t overwhelmed, cases are clearly informative, especially once we are out of the phase of rapid growth. And yeah, Sweden and California have both leveled off, so deaths per day should start dropping soon and the cumulative death plots should flatten. I’m still not going to breathe easy until I see that happen — just worried about various ways infections can fail to convert to cases but still lead to death — but I agree it looks like it’s coming soon.

Daniel –

Isn’t it critical to consider the ratio of tests conducted to cases identified before trying to infer future growth?

Sure, but Sweden seems to have started testing earlier than the US and grown quite quickly though not quite as fast as the US, so I don’t think they’ve saturated their testing capacity.

swedish vs us testing

Thanks for the link. I’ll check it out.

I was looking at Worldometer, and just eyeballing, it looked like their ratio of tests per million to cases per million was relatively low compared to other countries with high cases per million rates.

This is great contextual info. Thanks much!

BTW, I’d still guess a lot more travel between Lombardy and other countries in Western Europe than to Sweden. One of the reasons I’m skeptical of cross country comparisons to evaluate policy effectiveness without better data and a lot of control of potentially explanatory variables.

The pull to see patterns and draw conclusions about causality is very strong. The antidote to that I a better data and control.

Definitely Switzerland is more connected to Lombardy than Sweden. Over 65’000 people cross(ed) the border daily to work in the Italian-speaking canton of Ticino. Population 350’000, 2900 cases and 270 deaths. It may make more sense to compare Sweden to other Nordic countries than to Switzerland.

Well, it depends on whether you account for the differences between the Nordic countries and the regions therein. And just chance and random distribution. The outbreak in Sweden is happening in Stockholm, and other regions of Sweden have seen very little of Covid in comparison. Stockholm is with 1.3 million inhabitants (2.4 m metro) the most populated Nordic city (it calls itself the capital of Scandinavia). Swedish schools have a winter/spring break especially meant for doing winter sports (it’s called “sport break”) in February, but different regions have their break different weeks due to different climates. Stockholm had its winter sport holiday late February, so thousands of people travelled from Stockholm to Italy and the alps. Schools in other Nordic countries do not have this particular tradition.

So odds of Scandinavia seeing the first large outbreak in Stockholm were pretty low.

Also, I think it’s a mistake to count deaths or cases per capita this early. And it is still very, very early with this virus. Thing is, an outbreak grows in absolute numbers, with each one person spreading the contagion to X others. It also has a kind of speed, set by parameters such as when and how long the virus is contagious and it’s incubation period. It does not care how borders are drawn. Someone used the analogy of a forest fire, it does not matter how big the forest is or what different parts of the forest are named. It burns until it runs out of trees. It just takes a longer time to burn 25% of a largely defined area compared to a smaller one. And the absolute number of burned down trees could be the same.

Can you imagine how absurdly, impossibly fast the virus would have had to spread in the US to infect the same percentage of US 327 million people in the same time frame as it infected 10 million Swedes? Maybe comparing outbreak to outbreak would be more useful. But then you’d still have to account for density, demographics, climate, holidays, infrastructure…

I’m not sure any useful comparisons between countries can be done at this point.

And you can slow the virus down, but no one thinks you can eradicate it. It will take years before a vaccine is not only developed, but distributed. If we even get there at all.

“Can you imagine how absurdly, impossibly fast the virus would have had to spread in the US to infect the same percentage of US 327 million people in the same time frame as it infected 10 million Swedes?”

That’s just 5 doublings. With 3 days per doubling, it’s sufficient for the virus to have reached the US two weeks before it reached Sweden. Exponential growth is funny that way.

Consider an old riddle: imagine a pond with water lilies. The water lilies grow unchecked, there was one lily on the 1st day, 2 lilies on the 2nd day, 4 lilies on the 3rd day, 8 lilies on the 4th day, etc. The pond is completely covered with lilies on the 18th day. When was the pond half covered?

Mendel –

> Consider an old riddle: imagine a pond with water lilies. The water lilies grow unchecked, there was one lily on the 1st day, 2 lilies on the 2nd day, 4 lilies on the 3rd day, 8 lilies on the 4th day, etc. The pond is completely covered with lilies on the 18th day. When was the pond half covered?

Thanks. What a great way to get people to think about exponential growth.

Ani-

Thanks for that information.

Although I’m skeptical that in the end the same % of a given population will get infected irrespective of interventions, I will point out that there may be any variety of advantages to slowing the rate of spread, including the potential of reducing fatality rates from the development of therapeutics and preventing hospitals and healthcare workers from getting overwhelmed snd/or exhausting resources

I don’t think any of that suggests that Sweden is more comparable to Switzerland than to other Nordic countries.

And, from the Wikipedia numbers at least, Stockholm doesn’t seem so different from Copenhagen. The population of the urban area is 22% higher (1.6mn vs 1.3mn) but it’s also less dense (4200 vs 4500 per km2). For the metro area the population is 15% higher but with a much lower density (2.4mn, 360 per km2 vs 2.1mn, 1200 per km2).

I can’t find how many cases happened in the Copenhagen but on March 11 when the Danish government announced the closure of schools and other measures, there were 516 cases reported in the country. They were 620 in Sweden, including 266 in Stockholm county. Per 100’000 there were 9 cases in Denmark, 6 in Sweden, 11 in Stockholm county.

It also seems unfair to say that the outbreak is happening in Stockholm only, every county has now more cases reported per capita than Stockholm had one month ago.

Indeed. If you want a solid couple for a comparison, take Finland vs. Sweden. The former has followed the de facto standard restrictive approach, while the latter has followed its unique path. But both societies are pretty much similar in all relevant dimensions.

But we neeed to wait a year to see what the deaths are – Finland haven’t changed the 0.2% CFR, just the dates.

Agreed. In such decision making in face of so much uncertainty, it seems to me that a guiding principle should be to hedge against the largest categories of downside risk, even low probability high damage function risk. Of course, there there is huge downside risk to shutting down the economy.

It’s not hard to get an idea of how things are going in a country as a whole if you look at the fractional rate of change of new cases per day. This relates directly to the R0 number, the number of new cases one infected person causes. Yes, maybe there are ten or 20 unknown cases for every one confirmed, but as long as we can be consistent in using confirmed cases, we can use the published data.

Here’s how the basic calculation goes. The actual number will presumably vary from country to country, if you have a way to discover what the underlying number are. A value of R0 > 1.0 means exponential increase in the case count, a number less than 1.0 means the new cases are dwindling. We’d hope to see a number much less than 1.

Suppose R0 = 3. We often read that it’s in the range 2.5 – 3. And let’s take the period during which a person can pass on the disease is 10 days. Yes, we hear 14 days, but that’s an outside range. You have about 5 days where they don’t have symptoms and another 5 days during which they are clearly sick. If they get very sick, either they go to the hospital or other people are more careful around them. So about ten days.

Therefore an infected person will infect about 3 / 10 = 0.3 people /day. That is a fractional infection rate of 30%/day. In the US after the initial pulse of infections, that’s just about the number we had for several weeks. If continued, a 30% growth rate would lead to a frightening number of cases.

An R0 of 1.0 would mean that the growth curve has “flattened” – that it is no longer growing. For a nuclear reactor, it would be the regime of constant power. The fractional daily rate for this condition would be 0.3 / 3 = 0.1, or 10%/day growth rate. If you look at the data for the US, sure enough, the daily growth curve becomes just about flat at about the 0.1 value.

So for the US data, at any rate, assigning an initial R0 value of 3 seems fairly close to the mark. I’ve seen the same thing for many other countries, too, but not all of them. The current value for the US is around 0.035, or 3.5% / day. That difference would be what social distancing, closing down parts of the economy, and the other things we’ve been doing have achieved.

These data are taken from the John Hopkins time series data, BTW.

If you look at the data for Sweden, there is some weird behavior in the confirmed case count – now apparently taken care of -, but the death counts look normal (i.e., like many other countries) except for those large ups and downs that others mentioned in earlier comments. In particular, the fractional daily growth rates track the U.S curve very well (except for the ups and downs) except for one thing.

After the Swedes experienced an initial surge in deaths, their response as shown by the fractional daily deaths started dropping nearly two weeks sooner than in the US relative to its initial pulse (the big pulse came about earlier in the US than in Sweden).

Hi there, just two pieces of information that are important to consider when evaluating Sweden. Important to remember is that countries count COVID deaths in different ways, which makes the figures very seldom easily comparable. In contrast to most countries (e.g., the Netherlands, the UK, and Norway), Sweden (just like Belgium) includes deaths at nursing homes, at home, etc., and not just “hospital deaths” (which is the case for many other countries). That makes a very large difference for the numbers (around 1/3 of totals). In addition, and perhaps even more important, the Swedish count is of “deaths with COVID” (someone died, and had the virus), it is not a count of “deaths of COVID” (someone died, had the virus, and the cause of death was deemed to have been the virus). The issue of how many who died because of COVID instead of just being infected by COVID, will be sorted out later. Thus, had other countries counted their COVID deaths in the Swedish way, Sweden’s figures would have looked much less serious when compared to other countries. Unfortunately, these Swedish counting principles are almost never mentioned in news articles about COVID in Sweden. Note, what Sweden still has many unfilled ICU beds, and the healthcare system (while strained in some areas) is overall not strained: the system I coping.

Birger, thanks, this is a good point, and one that I know the Swedish health authorities have emphasized. But Sweden is not alone in this definition; for instance ” In Italy, any death in a patient with positive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing for SARS-CoV-2 is considered COVID-19 related”; and for the past week the U.S. has been counting both probably and confirmed COVID-19 deaths as defined by this standard: “A confirmed case or death is defined by meeting confirmatory laboratory evidence for COVID-19. A probable case or death is defined by i) meeting clinical criteria AND epidemiologic evidence with no confirmatory laboratory testing performed for COVID-19; or ii) meeting presumptive laboratory evidence AND either clinical criteria OR epidemiologic evidence; or iii) meeting vital records criteria with no confirmatory laboratory testing performed for COVID19.” Several other countries have either always used, or have switched to using, criteria not very different from Sweden’s. Maybe most have, I don’t know. Anyway I think this is a good point to keep in mind but I don’t think it changes the overall picture much, at least with numbers from recent days.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/21/world/coronavirus-missing-deaths.html

To be fair it does seem like Sweden is doing a better job of accounting for its Covid-19 deaths. At least by looking at all-cause mortality Sweden does not have a large number of unexplained excess deaths sofar.

Nice post Phil, thanks for going to all the effort.

I can kinda see why you lost interest in it: the mystery revealed banality. Sweden is using a novel approach to have roughly the same disaster, at least in terms of lives lost.

But IMO it’s better than you make it out to be, since they won’t have to repay the borrowing. Very *very* roughly the US has borrowed $3Trillion, which works out to roughly $10K per person. That’ll take some healthcare out of your future.

Phil:

Good job. Nice to have some level-headed overall assessment. Things have gotten way too complicated to try to do this by oneself.

Phil:

Sweden has a substantial immigrant population. Does that factor in any way? I’ve heard immigrant areas have been particularly hard hit. The most hard-hit European countries also look to have substantial immigrant populations.

Hi, As a Swede, I can confirm that Syrians and Somalis are highly overrepresented among the “deaths with Corona”, due to highly localized disease spread in some areas in Stockholm, but their proportion of the totals is still small. While 50% of Swedish households are composed of singles (social distancing by default), the opposite is true for Somalis and Syrians, where families (writ large) can be very extensive, large and close (no social distancing by default). At the aggregate, the “deaths with COVID” (not to be confused with “deaths of COVID”) are almost exclusively in the age span >70 years old.

The group who fall under the heading “immigrant” in a country like Sweden live in the same socioeconomic niche as non-privileged minority groups in USA or any other wealthy country. As such, I would be willing to bet they will be battered by this much more badly than the middle-class and wealthy. It’s virtually axiomatic that in any society economic or health problems fall heaviest on those at the bottom of the socioeconomic pecking order.

+1

Actually I haven’t seen too much data on ethnicity or immigration status, the thing that stands out to me is that 90% of fatalities are over the age of 60, and a majority of those are over age 80, so I’m not sure how that jives with immigration status or ethnicity, but my guess is that the affected nursing home population is overwhelmingly native (e.g., European in Europe, American in the US).

Also relevant: what percentage of the staff of nursing homes consists of immigrant?

> Yes, their per capita death count is still increasing faster than that of most of their peers, but not by a huge amount, and presumably they think they can bring the growth rate down soon

> They might end up in the top eight or top five countries in deaths per capita — they’ll be number 9 in a few days

Eeeh, I’m not super convinced by the line fits. At least if we’re going by the stuff plotted it doesn’t seem obvious to me that they’ll move up the ranks (though it doesn’t look like they’ll move down either). I could easily be reading it wrong though.

The plot shows deaths, not deaths per capita. Switzerland’s deaths per capita is increasing 45% per 8 days, Sweden is increasing 100% per 8 days, and deaths per million is 165 (Switzerland) versus 155 (Sweden). Multiply the first number by 1.45 and the second by 2 and you have an estimate of where they’ll be next week. That’s not a guarantee, of course — Sweden could start to flatten out tomorrow, or maybe already has (hard to know, given the large ‘weekend effect’ in the counts, which takes days to resolve) — but if I were to bet on something so macabre I’d be betting for Sweden to overtake Switzerland.

I found this chart helpful in thinking about the Swedish reporting delay.

The gray bars are a simple constant approximation to the number of lagged reports with a given delay, if I understood the R code right. Based on that model, Sweden is also past the (first) peak.

https://adamaltmejd.se/covid/

Very helpful indeed, thanks!

Phil:

A lot of discussion assumes a one-size-fits-all thinking. But there is a h**k of a lot of heterogeneity. Is it possible to accomplish a lot by focusing more narrowly? For instance, banning groups of more than 10 or 5 seems like it would accomplish a lot. And making people stay 6 feet apart would also accomplish a lot more. Also, there seems to be little transmission by touch. Also, supers-spreaders seem to be a very big part of this.

My question is, would it be possible to accomplish a large amount with very narrowly focused prohibitions?

I didn’t say this very well. Let me try the inverse.

Are there things we can just ignore (rather than be super careful about everything) because the risk is so low? Can we just forget about gloves and touching things? Can two-person HVAC teams forget about masks (just stay away from the customer)? Can we not worry about hanging out with good friends if no one seems to be sick? Can we play non-contact outdoor sports without worrying about anything? Can we eat takeout food without any precautions?

All good questions, Terry, by which I mean I don’t know the answers…although I did read an article by a doctor that says transmission from food is unlikely, and hey, if a doctor says it it must be true.

It’s obvious that activities aren’t either ‘safe’ or ‘risky’, there’s a continuum; also the risk doesn’t just depend on the activity in a generic sense (even conditional on an infected person being involved) but on the details of how the activity is performed. But how to determine which ones are most risky, and here to draw the line between what is and isn’t acceptable..your guess is as good as mine, or quite possibly better.

+1 to second paragraph

To Phil the blog post author,

I have a minor disagreement with one of your behavioral assumptions. You describe the virus response measures taken by a company who services HVAC in California. It seems responsible and well-reasoned, as a way to mitigate risk. It is my informed judgement that their changes to business operations, to minimize the chances of virus infection, will be effective, which was your conclusion as well. Next, you say,

Phil, why would you not trust companies in the United States to make the decision to shut down if low-transmission work is impossible? You just gave an example of an exemplary American HVAC company who took all sorts of measures, voluntarily, to ensure a safe environment for workers. California is part of the United States.

The latter part of the passage you quoted sounds like uh Swedish exceptionalism to me. No, that’s an overstatement. Yet it is naive to readily accept the word of Swedish politicians who claim that Swedes have superior morality compared to other nations. And then you extrapolate to the US, that such upstanding and ethical behavior is inconceivable.

Andrew wrote a post about avoiding political bias in analyzing the COVID-19 pandemic and an effective response. The United States is not a failed state, without rule of law, and utterly lacking in business ethics. If that were the case, our financial markets wouldn’t be the most liquid, deep, efficient, and transparent in the world. Be careful of preconceived biases.

Thank you for the link to world rankings of per capita-adjusted COVID-19 deaths by nation. I was glad to note that the United States is in position #12 with the following more ethical, responsible, trustworthy nations (well, some of them, e.g. Sweden) having higher death rates in ascending order of lethality: Ireland, Sweden, Switzerland, Netherlands, UK, France, Italy, Spain, Andorra, San Marion, and Belgium. We’re not doing so bad, despite all the blame heaped on Dr. Fauci and Donald Trump and Dr. Birx and the CDC.

Ellie,

Standing ten feet from each other, the owner of the HVAC company and I had a long conversation in which we discussed the coronavirus response and how his company is handling it. He said he has had trouble getting some of his employees to take the rules sufficiently seriously, but he admitted that he might have felt the same way except that his wife is a nurse so he (1) is worried about her, and (2) hears her stories about what the patients are going through. He also said that after the Bay Area counties had issued shutdown orders, but before California had done so, one of his employees went to Tahoe to spend the weekend snowboarding with friends at a ski resort. Actually they only did it on Saturday, since the ski places were all shut down the next day. But the point is that unless the place was shut down, they were doing it. One of my wife’s friends did the same thing on the same weekend, going to a shared ski house (5 couples) for the weekend, but having it shut down after one day.

And of course there are all those mayors and governors who tweeted messages encouraging people to go about business as usual, keep eating in restaurants, get out and keep the economy going, and so on, after cases and deaths had already started to climb. Oh, and churches that had services in which they encouraged people to hug each other.

I could go on and on, but all that will happen is that someone will say “the plural of ‘anecdote’ is not ‘data.'” So maybe I can sum it up this way: I’m almost 55 years old, I’ve lived in the United States my whole life, I’m familiar with the culture here, and I don’t trust enough Americans to voluntarily take the steps that are needed in the present circumstances.

Didn’t see this mentioned, but Sweden counts include both died WITH Covid-19 and died FROM Covid-19.

Not all countries do that. Given Sweden can count very well, I don’t think they undercount.

Source: https://reason.com/2020/04/17/in-sweden-will-voluntary-self-isolation-work-better-than-state-enforced-lockdowns-in-the-long-run/?fbclid=IwAR3NuNujEopPCN-pOuFFK7KtbKN9GH0pI95RzEJpv8rE2Mpz0lc7JRbxwhs

Sweden definitely undercounts on any given day: the total number of deaths announced as of today, April 20, is too low. But they will revise today’s number upwards over the next few days or the next week until it is accurate. By then, though, several days will have passed, so the number of deaths announced as of April 25 will also be too low, initially. And so on. This is an issue in every country, as far as I know, but seems to be larger in Sweden than other places I’ve looked at.

Birger (above) made the same point about Sweden counting a wider range of deaths, but I think the difference is not that big for at least some other countries. See my comment to Birger above. Or perhaps I should say: yes Sweden counts COVID deaths differently from some countries, but not all. Many other countries also count everyone who died with a positive test, or even everyone who died with symptoms consisted with COVID-19 even if they weren’t tested.

I am not convinced that the Swedish reporting lag (as opposed to the weekend effect) is greater than in other places, especially ones thad consider cause of death rather than diagnosis status in their reporting.

Does anyone know of any other country/state that reports the actual dates of COVID deaths (and ideally also their reporting dates)?

I don’t remember anyone including reporting dates but deaths by date are not that unusual. See for example New York City (daily counts chart in www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page ) and Switzerland (page 6 in http://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/fr/dokumente/mt/k-und-i/aktuelle-ausbrueche-pandemien/2019-nCoV/covid-19-lagebericht.pdf.download.pdf/COVID-19_Situation_epidemiologique_en_Suisse.pdf ).

That can accentuate the raw numbers but in terms of the *exponential rate of growth*, I suspect it might actually artificially shrink it. Basically other countries will see the death toll rise faster as health systems break down and more vulnerable populations are reached, but if in Sweden you add a fixed constant non-covid death rate to the infecteds, then that cushions the numbers.

In all these discussions people seem to be advocating an implicit underlying ideal curve for fatalities. It’s not clear what the justification for that curve is.

Maybe everyone doesn’t share Phil