A correspondent writes:

I thought you might care to comment on a rebuttal in today’s HealthAffairs. I find it a poor non-defense that relies on “1000s of studies used our measure and found it valid”, as well as attacks on the critics of their work.

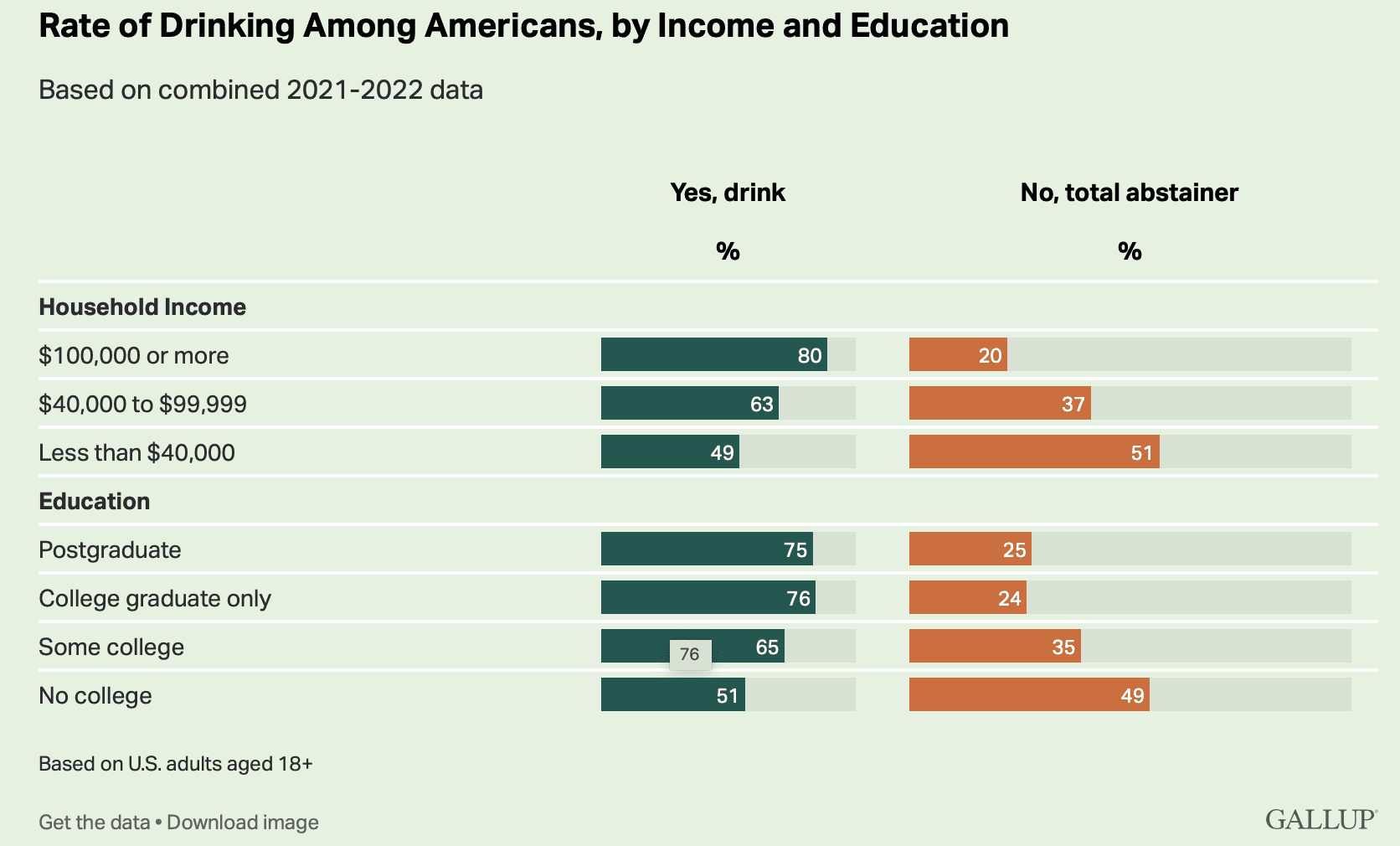

The issue began when the Center of Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) decided to explore a health equity payment model called ACO-REACH. CMS chose a revenue neutral scheme to remove some dollars from payments to providers serving the most-advantaged people and re-allocate those dollars to the most disadvantaged. Of course, CMS needs to choose a measure of poverty that is 100% available and easy to compute. These requirements limit the measure to a poverty index available from Census data.

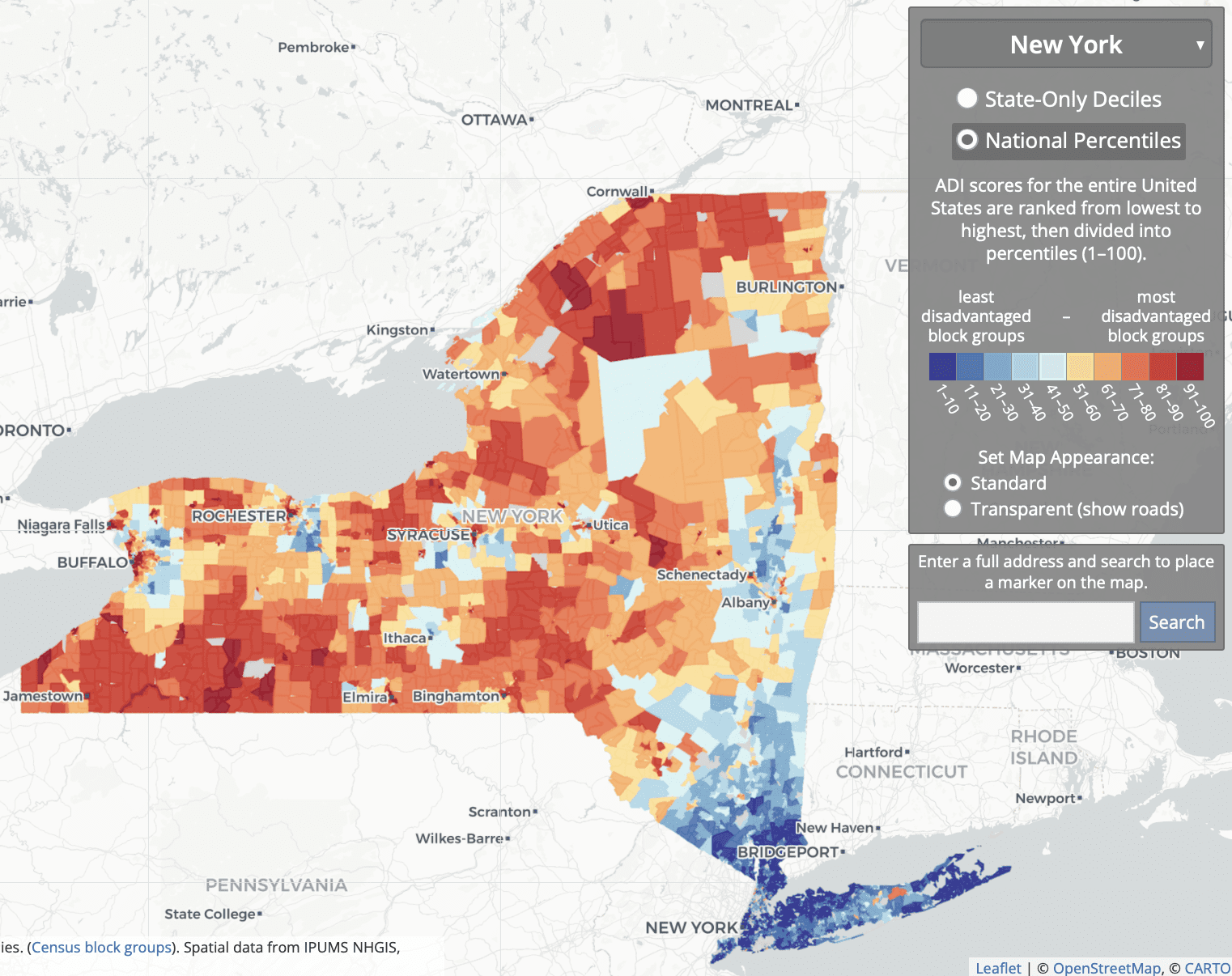

CMS chose to use a common poverty index, University of Wisconsin’s Area Deprivation Index (ADI). Things got spicy earlier this year when some other researchers noticed that no areas in the Bronx or south-eastern DC are in the lowest deciles of the ADI measure. After digging into the ADI methods a bit deeper, it seems the issue is that the ADI does not scale the housing dollars appropriately before using that component in a principal components analysis to create the poverty index.

One thing I find perplexing about the rebuttal from UWisc is that it completely ignores the existence of every other validated poverty measure, and specifically the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index. Their rebuttal pretends that there is no alternative solution available, and therefore the ADI measure must be used as is. Lastly, while ADI is publicly available, it is available under a non-commercial license so it’s a bit misleading for the authors to not disclose that they too have a financial interest in pushing the ADI measure while accusing their critics of financial incentives for their criticism.

The opinions expressed here are my own and do not reflect those of my employer or anyone else. I would prefer to remain anonymous if you decide to report this to your blog, as I wish to not tie these personal views to my employer.

Interesting. I’d never heard of any of this.

Here’s the background:

Living in a disadvantaged neighborhood has been linked to a number of healthcare outcomes, including higher rates of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, increased utilization of health services, and earlier death1-5. Health interventions and policies that don’t account for neighborhood disadvantage may be ineffective. . . .

The Area Deprivation Index (ADI) . . . allows for rankings of neighborhoods by socioeconomic disadvantage in a region of interest (e.g., at the state or national level). It includes factors for the theoretical domains of income, education, employment, and housing quality. It can be used to inform health delivery and policy, especially for the most disadvantaged neighborhood groups. “Neighborhood” is defined as a Census block group. . . .

The rebuttal

Clicking on the above links, I agree with my correspondent that there’s something weird about the rebuttal article, starting with its title, “The Area Deprivation Index Is The Most Scientifically Validated Social Exposome Tool Available For Policies Advancing Health Equity,” which elicits memories of Cold-War-era Pravda, or perhaps an Onion article parodying the idea of someone protesting too much.

The article continues with some fun buzzwords:

This year, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) took a ground-breaking step, creating policy aligning with multi-level equity science and targeting resources based on both individual-level and exposome (neighborhood-level) disadvantage in a cost-neutral way.

This sort of bureaucratic language should not in itself be taken to imply that there’s anything wrong with the Area Deprivation Index. A successful tool in this space will get used by all sorts of agencies, and bureaucracy will unavoidably spring up around it.

Let’s read further and see how they respond to the criticism. Here they go:

Hospitals located in high ADI neighborhoods tend to be hit hardest financially, suggesting health equity aligned policies may offer them a lifeline. Yet recently, CMS has been criticized for selecting ADI for use in its HEBA. According to behavioral economics theory, potential losers will always fight harder than potential winners, and in a budget-neutral innovation like ACO REACH there are some of both.

I’m not sure the behavioral economics framing makes sense here. Different measures of deprivation will correspond to different hospitals getting extra funds, so in that sense both sides in the debate represent potential winners and losers from different policies.

They continue:

CMS must be allowed time to evaluate the program to determine what refinements to its methodology, if any, are needed. CMS has signaled openness to fine-tune the HEBA if needed in the future. Ultimately, CMS is correct to act now with the tools of today to advance health equity.

Sure, but then you could use one of the other available indexes, such as the Social Deprivation Index or the Social Vulnerability Index, right? It seems there are two questions here: first, whether to institute this new policy to “incentivize medical groups to work with low-income populations”; second, whether there are any available measures of deprivation that make sense for this purpose; third, if more than one measure is available, which one to use.

So now on to their defense of the Area Deprivation Index:

The NIH-funded, publicly availably ADI is an extensively validated neighborhood-level (exposome) measure that is tightly linked to health outcomes in nearly 1000 peer-reviewed, independent scientific publications; is the most commonly used social exposome measure within NIH-funded research today; and undergoes a rigorous, multidisciplinary evaluation process each year prior to its annual update release. Residing in high ADI neighborhoods is tied to biological processes such as accelerated epigenetic aging, increased disease prevalence and increased mortality, poor healthcare quality and outcomes, and many other health factors in research studies that span the full US.

OK, so ADI is nationally correlated with various bad outcomes. This doesn’t yet address the concern of the measure having problems locally.

But they do get into the details:

A recent peer-reviewed article argued that the monetary values in the ADI should be re-weighted and an accompanying editorial noted that, because these were “variables that were measured in dollars,” they made portions of New York State appear less disadvantaged than the authors argued they should be. Yet New York State in general is a very well-resourced state with one of the ten highest per capita incomes in the country, reflected in their Medicaid Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP). . . .

Some critics relying on face validity claim the ADI does not perform “well” in cities with high housing costs like New York, and also California and Washington, DC, and suggest that a re-weighted new version be created, again ignoring evidence demonstrating the strong link between the ADI and health in all kinds of cities including New York (also here), San Francisco, Houston, San Antonio, Chicago, Detroit, Atlanta, and many others. . . .

That first paragraph doesn’t really address the question, as the concerns about the South Bronx not having a high deprivation index are about one part of New York, not “New York State in general.” But the rebuttal article does offer two links about New York specifically, so let me take a look:

Associations between Amygdala-Prefrontal Functional Connectivity and Age Depend on Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status:

Given the bimodal distribution of ADI percentiles in the current sample, the variable was analyzed in three groups: low (90–100), middle (11–89), and high neighborhood SES.

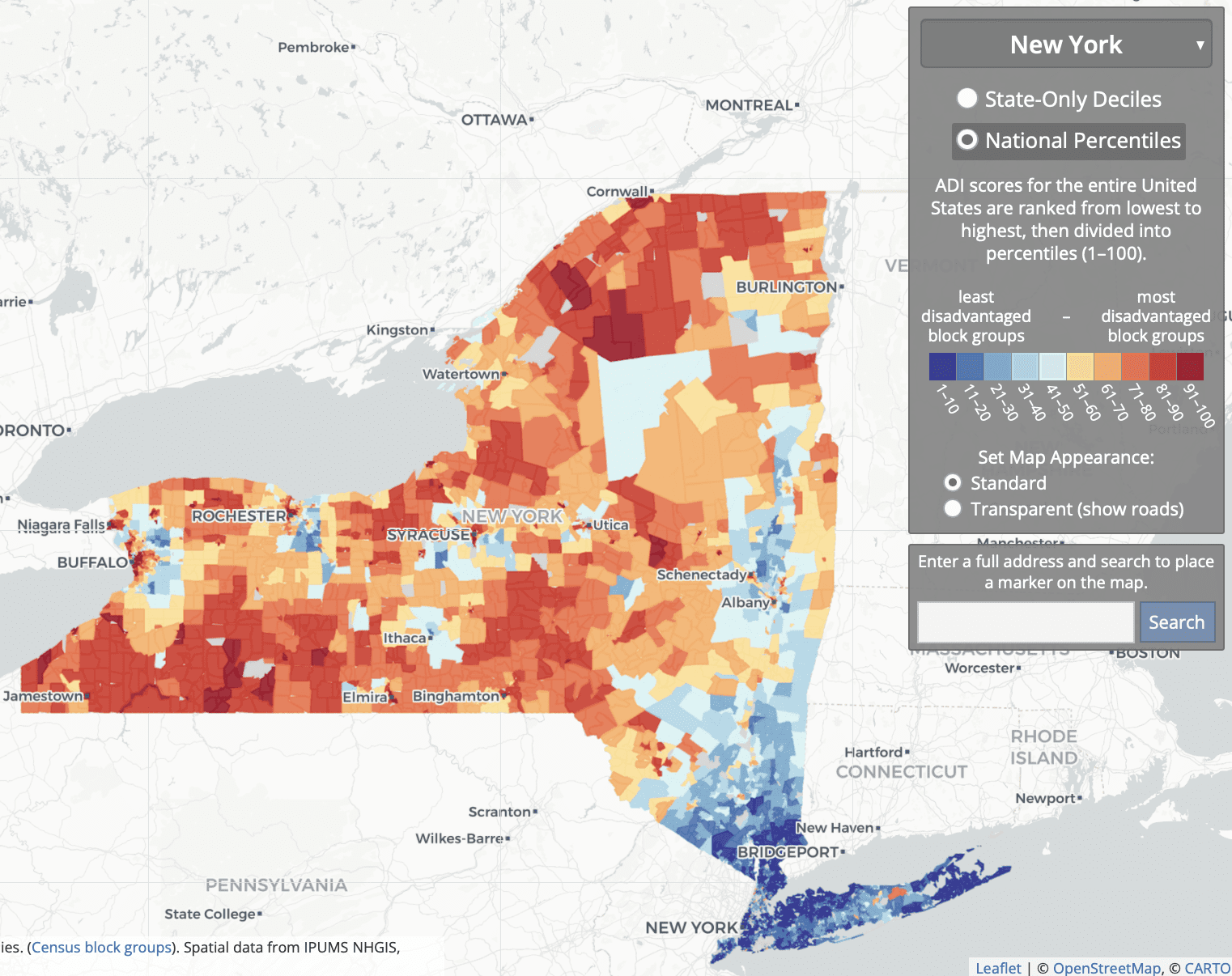

To get a sense of things, I went to the online Neighborhood Atlas and grabbed the map of national percentiles for New York State:

So what they’re doing is comparing some rich areas of NYC and its suburbs; to some low- and middle-income parts of the city, suburbs, and upstate; to some low-income rural and inner-city areas upstate.

Association Between Residential Neighborhood Social Conditions and Health Care Utilization and Costs:

Retrospective cohort study. Medicare claims data from 2013 to 2014 linked with neighborhood social conditions at the US census block group level of 2013 for 93,429 Medicare fee-for-service and dually eligible patients. . . . Disadvantaged neighborhood conditions are associated with lower total annual Medicare costs but higher potentially preventable costs after controlling for demographic, medical, and other patient characteristics. . . . We restricted our sample to patients with 9-digit residential zip codes available in New York or New Jersey . . .

I don’t see the relevance of these correlations to the criticisms of the ADI.

To return to our main thread, the rebuttal summarizes:

The ADI is currently the most validated scientific tool for US neighborhood level disadvantage. This does not mean that other measures may not eventually also meet this high bar.

My problem here is with the term “most validated.” I’m not sure how to take this, given that all this validation didn’t seem to have shown that problem with the South Bronx etc. But, sure, I get their general point: When doing research, better to go with the devil you know, etc.

The rebuttal authors add:

CMS should continue to investigate all options, beware of conflicts of interest, and maintain the practice of vetting scientific validated, evidence-based criteria when selecting a tool to be used in a federal program.

I think we can all agree on that.

Beyond general defenses of the ADI on the grounds that many people use it, the rebuttal authors make an interesting point about the use of neighborhood-level measures more generally:

Neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage is just as (and is sometimes more) important than individual SES. . . . These factors do not always overlap, one may be high, the other low or vice versa. Both are critically important in equity-focused intervention and policy design. In their HEBA, as aligned with scientific practice, CMS has included one of each—the ADI captures neighborhood-level factors, and dual Medicare and Medicaid eligibility represents an individual-level factor. Yet groups have mistakenly conflated individual-level and neighborhood-level factors, wrongly suggesting that neighborhood-level factors are only used because additional individual factors are not readily available.

They link to a review article. I didn’t see the reference there to groups claiming that neighborhood-level factors are only used because additional individual factors are not readily available, but I only looked at that linked article quickly so I probably missed the relevant citation.

The above are all general points about the importance of using some neighborhood-level measure of disadvantage.

But what about the specific concerns raised with the ADI, such as the labeling most of the South Bronx as being low disadvantage (in the 10th to 30th percentile nationally)? Here’s what I could find in the rebuttal:

These assertions rely on what’s been described as “the weakest of all possible arguments”: face validity—defined as the appearance of whether or not something is a correct measurement. This is in contrast to empirically-driven tests for construct validity. Validation experts universally discredit face validity arguments, classifying them as not legitimate, and more aligned with “marketing to a constituency or the politics of assessment than with rigorous scientific validity evidence.” Face validity arguments on their own are simply not sufficient in any rigorous scientific argument and are fraught with potential for bias and conflict of interest. . . .

Re-weighting recommendations run the risk of undermining the strength and scientific rigor of the ADI, as any altered ADI version no longer aligns with the highly-validated original Neighborhood Atlas ADI methodology . . .

Some have suggested that neighborhood-level disadvantage metrics be adjusted to specific needs and areas. We consider this type of change—re-ranking ADI into smaller, custom geographies or adding local adjustments to the ADI itself—to be a type of gerrymandering. . . . A decision to customize the HEBA formula in certain geographies or parts of certain types of locations will benefit some areas and disservice others . . .

I disagree with the claim that face validity is “the weakest of all possible arguments.” For example, saying that a method is good because it’s been cited thousands of times, or saying that local estimates are fine because the national or state-level correlations look right, those are weaker arguments! And if validation experts universally discredit face validity arguments . . . ummmm, I’m not sure who are the validation experts out there, and in any case I’d like to see the evidence of this purportedly universal view. Do validation experts universally think that North Korea has moderate electoral integrity?

The criticism

Here’s what the critical article lists as limitations of the ADI:

Using national ADI benchmarks may mask disparities and may not effectively capture the need that exists in some of the higher cost-of-living geographic areas across the country. The ADI is a relative measure for which included variables are: median family income; percent below the federal poverty level (not adjusted geographically); median home value; median gross rent; and median monthly mortgage. In some geographies, the ADI serves as a reasonable proxy for identifying communities with poorer health outcomes. For example, many rural communities and lower-cost urban areas with low life expectancy are also identified as disadvantaged on the national ADI scale. However, for parts of the country that have high property values and high cost of living, using national ADI benchmarks may mask the inequities and poor health outcomes that exist in these communities. . . .

They recommend “adjusting the ADI for variations in cost of living,” “recalibrating the ADI to a more local level,” or “making use of an absolute measure such as life expectancy rather than a relative measure such as the ADI.”

There seem to be two different things going on here. The first is that ADI is a socioeconomic measure, and it could also make sense to include a measure of health outcomes. The second is that, as a socioeconomic measure, ADI seems to have difficulty in areas that are low income but with high housing costs.

My summary

1. I agree with my correspondent’s email that led off this post. The criticisms of the ADI seem legit—indeed, they remind me a bit of the Human Development Index, which a similar problem of giving unreasonable summaries that can be attributed to someone constructing a reasonable-seeming index and then not looking into the details; see here for more. There was also the horrible, horrible Electoral Integrity Index, which had similar issues of face validity that could be traced back to fundamental issues of measurements.

2. I also agree with my correspondent that the rebuttal article is bad for several reasons. The rebuttal:

– does not ever address the substantive objections;

– doesn’t seem to recognize that, just because a measure gives reasonable national correlations, that doesn’t mean that it can’t have serious local problems;

– leans on an argument-from-the-literature that I don’t buy, in part out of general distrust of the literature and in part because none of the cited literature appears to address the concerns on the table;

– presents a ridiculous argument against the concept of face validity.

Face validity—what does that mean?

Let me elaborate upon that last point. When a method produces a result that seems “on its face” to be wrong, that does not necessarily tell us that the method is flawed. If something contradicts face validity, that tells us that it contradicts our expectations. It’s a surprise. One possibility is that our expectations were wrong! Another possibility is that there is a problem with the measure, in which case the contradiction with our expectations can help us understand what went wrong. That’s how things went with the political science survey that claimed that North Korea was a moderately democratic country, and that’s how things seem to be going with the Area Deprivation Index. Even if it has thousands of citations, it can still have flaws. And in this case, the critics seem to have gone in and found where some of the flaws are.

In this particular example, the authors of the rebuttal have a few options.

They could accept the criticisms of their method and try to do better.

Or they could make the affirmative case that all these parts of the South Bronx, southeast D.C., etc., are not actually socioeconomically deprived. Instead they kind of question that these areas are deprived (“New York State in general is a very well-resourced state”) but without quite making that claim. I think one reason they’re stuck in the middle is politics. Public health is in general coming from the left side of the political spectrum and, from the left, if an area is poor and has low life expectancy, you’d call it deprived. From the right, you could argue that these poor areas already get tons of government support and that all this welfare dependence just compounds the problem. From a conservative perspective, you might argue that these sorts of poor neighborhoods are not “deprived” but rather are already oversaturated with government support. But I don’t think we’d be seeing much of that argument in the health-disparities space.

Or they could make a content-low response without addressing the problem. Unfortunately, that’s the option they chose.

I have no reason to think they’ve chosen to respond poorly here. My guess is that they’re soooo comfortable with their measure, soooooo sure it’s right, that they just dismissed the criticism without ever thinking about it. Which is too bad. But now they have this post! Not too late for them to do better. Tomorrow’s another day, hey!

P.S. My correspondent adds:

The original article criticizing the ADI measure has some map graphic sins that any editor should have removed before publication. Here are some cleaner comparisons of the city data. The SDI measure in those plots is the Social Deprivation Index from Robert Graham Center.

Washington, D.C.:

New York City:

Boston:

San Francisco area: