In politics, as in baseball, hot prospects from the minors can have trouble handling big-league pitching.

Right after Sarah Palin was chosen as the Republican nominee for vice president in 2008, my friend Ubs, who grew up in Alaska and follows politics closely, wrote the following:

Palin would probably be a pretty good president. . . . She is fantastically popular. Her percentage approval ratings have reached the 90s. Even now, with a minor nepotism scandal going on, she’s still about 80%. . . . How does one do that? You might get 60% or 70% who are rabidly enthusiastic in their love and support, but you’re also going to get a solid core of opposition who hate you with nearly as much passion. The way you get to 90% is by being boringly competent while remaining inoffensive to people all across the political spectrum.

Ubs gives a long discussion of Alaska’s unique politics and then writes:

Palin’s magic formula for success has been simply to ignore partisan crap and get down to the boring business of fixing up a broken government. . . . It’s not a very exciting answer, but it is, I think, why she gets high approval ratings — because all the Democrats, Libertarians, and centrists appreciate that she’s doing a good job on the boring non-partisan stuff that everyone agrees on and she isn’t pissing them off by doing anything on the partisan stuff where they disagree.

Hey–I bet you never thought you’d see the words “boringly competent,” “inoffensive,” and “Sarah Palin” in the same sentence!

Prediction and extrapolation

OK, so what’s the big deal? Palin got a reputation as a competent nonpartisan governor but when she hit the big stage she shifted to hyper-partisanship. The contrast is interesting to me because it suggests a failure of extrapolation.

Now let’s move to baseball. One of the big findings of baseball statistics guru Bill James is that minor-league statistics, when correctly adjusted, predict major-league performance. James is working through a three-step process: (1) naive trust in minor league stats, (2) a recognition that raw minor league stats are misleading, (3) a statistical adjustment process, by which you realize that there really is a lot of information there, if you know how to use it.

For a political analogy, consider Scott Brown. When he was running for the Senate last year, political scientist Boris Shor analyzed his political ideology. The question was, how would he vote in the Senate if he were elected? Boris wrote:

We have evidence from multiple sources. The Boston Globe, in its editorial endorsing Coakley, called Brown “in the mode of the national GOP.” Liberal bloggers have tried to tie him to the Tea Party movement, making him out to be very conservative. Chuck Schumer called him “far-right.”

In 2002, he filled out a Votesmart survey on his policy positions in the context of running for the State Senate. Looking through the answers doesn’t reveal too much beyond that he is a pro-choice, anti-tax, pro-gun Republican. His interest group ratings are all over the map. . . .

All in all, a very confusing assessment, and quite imprecise. So how do we compare Brown to other state legislators, or more generally to other politicians across the country?

My [Boris’s] research, along with Princeton’s Nolan McCarty, allows us to make precisely these comparisons. Essentially, I use the entirety of state legislative voting records across the country, and I make them comparable by calibrating them through Project Votesmart’s candidate surveys.

By doing so, I can estimate Brown’s ideological score very precisely. It turns out that his score is -0.17, compared with her score of 0.02. Liberals have lower scores; conservatives higher ones. Brown’s score puts him at the 34th percentile of his party in Massachusetts over the 1995-2006 time period. In other words, two thirds of other Massachusetts Republican state legislators were more conservative than he was. This is evidence for my [Boris’s] claim that he’s a liberal even in his own party. What’s remarkable about this is the fact that Massachusetts Republicans are the most, or nearly the most, liberal Republicans in the entire country!

Very Jamesian, wouldn’t you say? And Boris’s was borne out by Scott Brown’s voting record, where he indeed was the most liberal of the Senate’s Republicans.

Political extrapolation

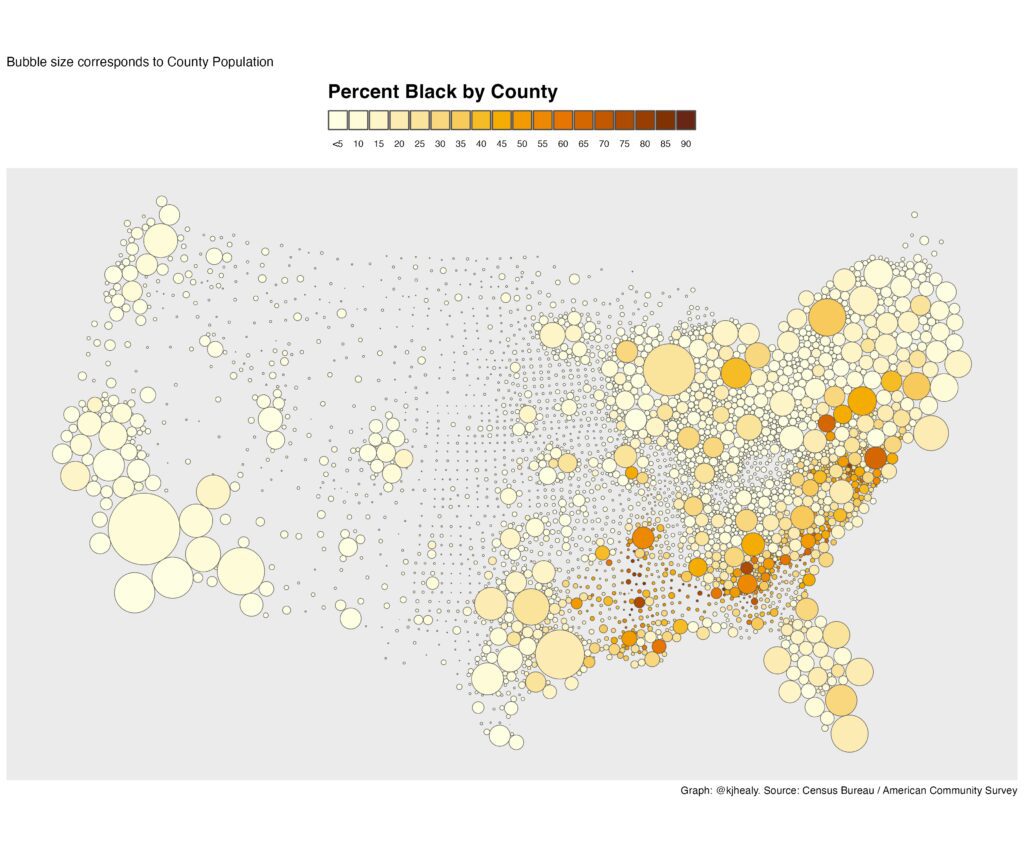

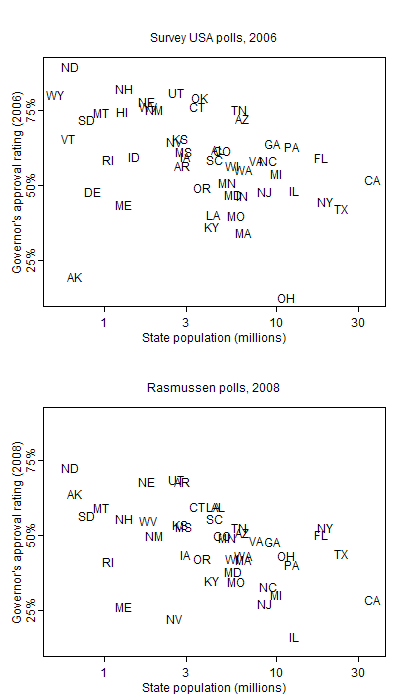

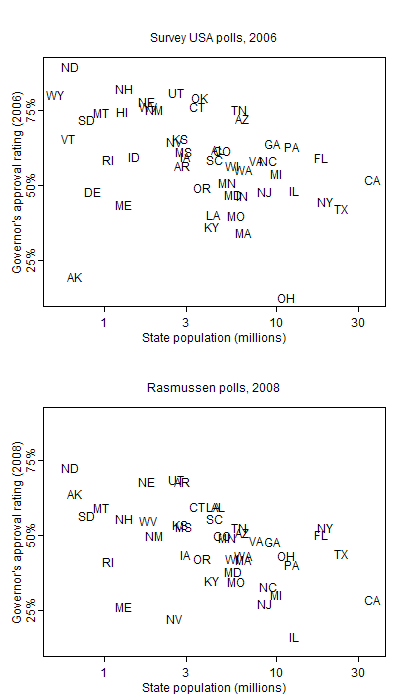

OK, now back to Sarah Palin. First, her popularity. Yes, Gov. Palin was popular, but Alaska is a small (in population) state, and surveys

find that most of the popular governors in the U.S. are in small states. Here are data from 2006 and 2008:

There are a number of theories about this pattern; what’s relevant here is that a Bill James-style statistical adjustment might be necessary before taking state-level stats to the national level.

The difference between baseball and politics

There’s something else going on, though. It’s not just that Palin isn’t quite so popular as she appeared at first. There’s also a qualitative shift. From “boringly competent nonpartisan” to . . . well, leaving aside any questions of competence, she’s certainly no longer boring or nonpartisan! In baseball terms, this is like Ozzie Smith coming up from the minors and becoming a Dave Kingman-style slugger. (Please excuse my examples which reveal how long it’s been since I’ve followed baseball!)

So how does baseball differ from politics, in ways that are relevant to statistical forecasting?

1. In baseball there is only one goal: winning. Scoring more runs than the other team. Yes, individual players have other goals: staying healthy, getting paid, not getting traded to Montreal, etc., but overall the different goals are aligned, and playing well will get you all of these to some extent.

But there are two central goals in politics: winning and policy. You want to win elections, but the point of winning is to enact policies that you like. (Sure, there are political hacks who will sell out to the highest bidder, but even these political figures represent some interest groups with goals beyond simply being in office.)

Thus, in baseball we want to predict how a player can help his team win, but in politics we want to predict two things: electoral success and also policy positions.

2. Baseball is all about ability–natural athletic ability, intelligence (as Bill James said, that and speed are the only skills that are used in both offense and defense), and plain old hard work, focus, and concentration. The role of ability in politics is not so clear. In his remarks that started this discussion, Ubs suggested that Palin had the ability and inclination to solve real problems. But it’s not clear how to measure such abilities in a way that would allow any generalization to other political settings.

3. Baseball is the same environment at all levels. The base paths are the same length in the major leagues as in AA ball (at least, I assume that’s true!), the only difference is that in the majors they throw harder. OK, maybe the strike zone and the field dimensions vary, but pretty much it’s the same game.

In politics, though, I dunno. Some aspects of politics really do generalize. The Massachusetts Senate has got to be a lot different from the U.S. Senate, but, in their research, Boris Shor and Nolan McCarty have shown that there’s a lot of consistency in how people vote in these different settings. But I suspect things are a lot different for the executive, where your main task is not just to register positions on issues but to negotiate.

4. In baseball, you’re in or out. If you’re not playing (or coaching), you’re not really part of the story. Sportswriters can yell all they want but who cares. In contrast, politics is full of activists, candidates, and potential candidates. In this sense, the appropriate analogy is not that Sarah Palin started as Ozzie Smith and then became Dave Kingman, but rather a move from being Ozzie Smith to being a radio call-in host, in a world in which media personalities can be as powerful, and as well-paid, as players on the field. Perhaps this could’ve been a good move for, say, Bill Lee, in this alternative universe? A player who can’t quite keep the ball over the plate but is a good talker with a knack for controversy?

Commenter Paul made a good point here:

How many at-bats long is a governorship? The most granular I could imagine possibly talking is a quarter. At the term level we’d be doing better making each “at-bat” independent of the previous. 20 or so at-bats don’t have much predictive value either. Even over a full 500 at-bat season, fans try to figure out whether a big jump in BABIP is a sign of better bat control or luck.

The same issues arise at very low at-bat counts too. If you bat in front of a slugger, you can sit on pitches in the zone. If you’ve got a weakness against a certain pitching style, you might not happen to see it. And once the ball is in the air, luck is a huge factor in if it travels to a fielder or between them.

I suspect if we could somehow get a political candidate to hold 300-400 different political jobs in different states, with different party goals and support, we’d be able to do a good job predicting future job performance, even jumping from state to national levels. But the day to day successes of a governor are highly correlative.

Indeed, when it comes to policy positions, a politician has lots of “plate appearances,” that is, opportunities to vote in the legislature. But when it comes to elections, a politician will only have at most a couple dozen in his or her entire career.

All the above is from a post from 2011. I thought about it after this recent exchange with Mark Palko regarding the political candidacy of Ron DeSantis.

In addition to everything above, let me add one more difference between baseball and politics. In baseball, the situation is essentially fixed, and pretty much all that matters is player ability. In contrast, in politics, the most important factor is the situation. In general elections in the U.S., the candidate doesn’t matter that much. (Primaries are a different story.) In summary, to distinguish baseball players in ability we have lots of data to estimate a big signal; to distinguish politicians in vote-getting ability we have very little data to estimate a small signal.