Back in the 1700s—JennyD can correct me if I’m wrong here—there was no standard style for writing. You could be discursive, you could be descriptive, flowery, or terse. Direct or indirect, serious or funny. You could construct a novel out of letters or write a philosophical treatise in the form of a novel.

Nowadays there are rules. You can break the rules, but then you’re Breaking. The. Rules. Which is a distinctive choice all its own.

Consider academic writing. Serious works of economics or statistics tend to be written in a serious style in some version of plain academic English. The few exceptions (for example, by Tukey, Tufte, Mandelbrot, and Jaynes) are clearly exceptions, written in styles that are much celebrated but not so commonly followed.

A serious work of statistics, or economics, or political science could be written in a highly unconventional form (consider, for example, Wallace Shawn’s plays), but academic writers in these fields tend to stick with the standard forms. The consensus seems to be that straight prose is the clearest way to convey interesting and important ideas. Serious popular writers such as Oliver Sacks and Malcolm Gladwell follow a slightly different formula, going with the magazine-writing tradition of placing ideas inside human stories. But they still, by and large, are trying to write clear prose.

When it comes to data graphics, though, we’re back in the freewheeling 1700s. Maybe that’s a good thing, I don’t know. But what I do know is there’s no standard way of displaying quantitative information, nor is there any acceptance of the unique virtues of the graphical equivalent of clear prose.

Serious works of social science nowadays use all sorts of data display, from showing no data at all, to tables, to un-designed Excel-style bar charts, to Cleveland-style dot and line plots, to creative new data displays, to ornamental information visualizations. The analogy in writing style would be if some journal articles were written in the pattern of Ezra Pound, others like Ernest Hemingway, and others in the style of James Joyce or William Faulkner.

I won’t try to make the case that everybody should do graphs the way I do. I accept that some people communicate with tables, others prefer infovis, and others prefer no quantitative information at all. I just think it’s interesting that prose style is so standardized—I’ve had submissions to journals criticized on the grounds that my writing is too lively!—but when it comes to display of data and models, it’s the Wild West.

For example . . .

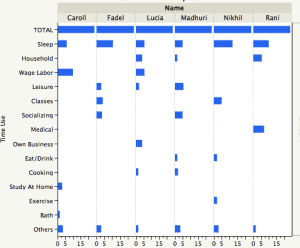

Kaiser points to this graph from the book Poor Economics by Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo:

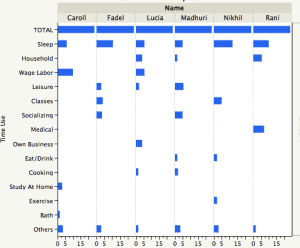

In case you’re curious what’s actually going on here, Kaiser helpfully replots the data in a readable form:

I’d be interested in what my infovis friends would say about this. The best argument I can think of in favor of the Banerjee and Duflo graph, besides its novelty and (perhaps) attractiveness, is that its very difficulty forces the reader to work, to put in so much effort to figure out what’s going on that he or she is then committed to learning more. In contrast, one might argue that Kaiser’s direct plot is so clear that the reader can feel free to stop right there. I don’t really believe this argument—I’d rather have the clear graph and convey more information—but that’s the best I can do.

That said, if a book has dozens of informative Kaiser-style graphs, I can see the benefit of having a few goofy ones just to mix things up a bit.