I was in the library the other day and saw a new book, Why are Jews Liberals?, by O.G. neoconservative Norman Podhoretz. This is right up my alley, research-wise, and so I took a look. I don’t think Podhoretz’s book will match the sales of Thomas Frank’s similar record of frustration, “What’s the Matter with Kansas?”–there are very few writers out there who can match Frank’s skill with the perceptive quip–but this new book has something to offer, if nothing else by presenting the view of an influential battler in the world of political ideas.

Podhoretz’s argument (here’s a quick summary) goes as follows. Jews in America vote overwhelmingly for Democrats, even though you’d expect from their income levels that Jews would lean Republican. Expanding this, Podhoretz gives three reasons why Jews should vote for Republicans:

1. The economy. Economic growth (which Podhoretz associates with conservative, business-friendly economic policies) is good in itself and also leads to a culture of affluence in which economically-successful minorities such as Jews are respected rather than resented.

2. Social issues. Socially conservative attitudes are more consistent with the Old Testament values of Judaism.

3. Israel. In recent decades, Podhoretz argues, the Republican Party and its allies in the conservative Christian evangelical movement have been more supportive of Israel than have the Democratic Party and its allies on the left.

Why are these three arguments not enough to convince a majority of Jews to go over to the dark side (as the recalcitrant majority of American Jews might say)? Podhoretz invokes the idea of false consciousness; in his words, “for [most American Jews], liberalism has become more than a political outlook. It has for all practical purposes superseded Judaism and become a religion in its own right.”

Thomas Frank thinks low-to-moderate-income Kansans should (almost) all be voting for Democrats; Norman Podhoretz thinks moderate-to-upper-income Jews should (almost) all be voting Republican.

A problem with Podhoretz’s argument is it proves too much. Why are Jews Democrats? Why is anyone a Democrat? Once you accept that conservative economic policies are good for growth, you’d think just about everyone would lean Republican on economic issues. In this sense, the argument in What’s the Matter with Kansas is more coherent: Thomas Frank can argue that Republican policies help the rich and hurt the poor (thus motivating a wealth gradient in how people vote, or how they should vote), but Podhoretz is not about to argue that, hey, Jews are financially successful so they should support the party of the rich. Instead, he goes for the larger freedom-and-opportunity pitch, which puts him in the uncomfortable position of basically arguing that, not just Jews, but everyone should be Republican. From this perspective, the answer is painfully clear: just as many Kansans disagree with Thomas Frank about what policies will be best for the national economy, similarly do many Jews, Catholics, Protestants, and others disagree with Norman Podhoretz about what are the policies that best promote economic freedom and opportunity.

Point #2 is social issues. I don’t know that much needs to be said here. Jews hold on average more socially liberal views than the average American, and I imagine this was true 50 and 100 years ago, as well. (To resolve this one, I guess we’d have to decide what counted as “social” issues back in 1909.) As Podhoretz himself notes, most Jews are not biblical literalists, and so the relevance of commandments and laws against adultery, homosexuality, etc., don’t seem so relevant. One might do better to turn the question around and ask why it is that so many Christians–who are not in general bound by Old Testament laws–have such strong socially conservative views.

Point #3 is Israel. I don’t want to get into this one at all–foreign policy is not my area of expertise. Perhaps it would suffice to say that experts as well as ordinary voters differ on what forms of U.S. engagement in the Middle East would be best.

My goal in making these points is not to shoot down any arguments–as Podhoretz notes, most Jews vote for Democrats, so he already realizes that many of the potential readers of his book disagree with him–but rather to locate his thinking into the larger context of popular and academic studies of American voters.

One might ask, why focus Jews at all? Why should we care about a voting bloc that represents only 2% of the population (and even if Jews turn out at a 50% higher rate than others, that would still be only 3% of the voters), most of whom are in non-battleground states such as New York, California, and New Jersey? Even in Florida, Jews are less than 4% of the population. I think a lot of this has to be about campaign contributions and news media influence. But, if so, the relevant questions have to do with intensity of opinions among elite Jews rather than aggregates. In that sense, Podhoretz’s book is a relevant document because of his connection to financial and media elites. (I don’t mean that in a conspiratorial sense; rather, it’s a measure of Podhoretz’s success as a writer and editor.)

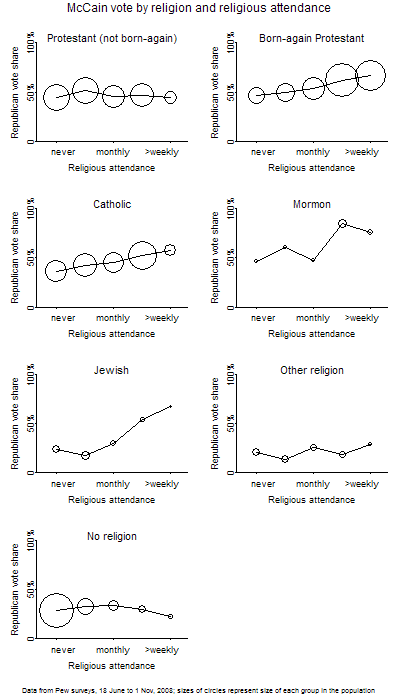

A mirror image to Jews are Mormons, another formerly-persecuted, now prosperous religion, representing 2% of population, living largely in non-battleground states, offering $ more than votes to the party they support, which in this case is overwhelmingly the Republicans. Here’s the story from 2008:

And here are some data from earlier elections. In Red State, Blue State we focus mostly on Catholics, Protestant (born-again and otherwise), and the non-religious, because these are the largest groups, and in our book we focus more on mass attitudes than on campaign contributions and media influence.

So what is my answer to Podhoretz’s question: Why are Jews liberals? I don’t really know how to answer the question of whether liberalism has become a “religion in its own right,” but one approach would be to compare Jews to other upper-income voters in urban-dominated states–people who, on average, have economically moderate and socially liberal views. It could also be interesting to compare to Mormons and other socially-marginalized ethnic and religious groups. Finally, there are national surveys that ask people what they consider are the most important issues determining their votes. To learn much about Jews in America, you can pool lots of surveys, or take some poll that oversamples Jews. I expect the information is out there and has been written up somewhere (maybe even Podhoretz refers to it in his book).

In the meantime, “Why are Jews Liberals?” can join “What’s the Matter with Kansas” in the False Consciousness shelf of your local bookstore or library. I imagine there must be many other books of this sort but I can’t think of them right now.

There's a book on the Bush women (I can't find the proper title) that belongs on your False Consciousness bookshelf.

Try inverting the question. For example, why are liberals Jewish? As you show, they're not. Religiously observant Jews are politically conservative. Why does Kansas vote Democratic? Maybe the Republicans moved to Texas to drill.

While there may be differing opinions on what is the best policy, which part is more supportive of Israel from an American Jewish perspective is an empirical matter. You could also survey Jews and ask them what policies they think Israel should follow and see which party has been most supportive of these policies.

There is a way that you could seperate out the liberalism as religion from a liberalism motivated by Judaism. You could ask Jews to justify their policy positions in religious terms. Not just that being Jewish requires caring good works but ask them to be more specific. Some will be stuck with broad principle, some won't think that their religion informs their policy positions and others will be able to provide an argument from Jewish law.

I suggest reading Milton Friedman's 'Capitalism and the Jews'.

In this essay, Friedman delves into why Jews have been largely hostile to Capitalism.

Guilt.

I don't think the phenomena has anything do with Judaism and everything to do with wealth and where most Jews reside (urban enclaves).

People need guilt offsets like the world needs carbon offsets.

Liberals took a cue from the catholic playbook and said hey rich people – do you feel guilty for all that wealth you have amassed? Well, this guilt can be offset as long as you prescribe to liberal ideals.

This guilt effect for the wealthy is particularly acute for the urban, highly educated elite, but less so for the suburban wealthy who are not as subjected to daily liberal preaching like their wealthy counterparts in urban areas.

This paper suggests some interesting connections between guilt and purchasing behavior:

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_i…

This is reading a lot into a small sample, but it looks like Jews who attend services at least weekly voted for McCain at rates comparable to born-agains who attend at least weekly. Maybe Podhoretz's 2nd point applies to that more observant group and the issue is that few Jews are highly observant. I bet that the regularly attending Jews are older, so it would be nice to control for that.

One Eyed Man: Yes, that was the sort of thing I was getting at in the second-to-last paragraph of my blog above. I haven't done such an analysis, and it wouldn't be trivial–you'd need to put together that large sample–but I'd guess that someone has looked into this.

Ariel: Interesting link. I still think, though, that the same argument would show that nearly everybody should prefer capitalism. To the extent that this is not true–for example, that someone like Paul Krugman favors government intervention in the economy–this looks to me more like a difference of opinion on the ability of pure capitalism to deliver the goods. I have no informed opinion on the merits in such a debate, but I don't see ethnic/religious identification as being the key issue here.

You (Gellman) could argue that the answer to his question is that Jews don't go to religious services often enough. I think a better argument is that Jews are the most urbanized ethnic group in America. Urban voters are Democratic voters. The modern Republican party is anti-intellectual, bigot-tolerant, and rural-based. I can't imagine why Jews lean heavily Democratic.

Oh no you di'n't. Did you just drop O.G. like Original Gangster?

I don't buy argument #2 straight out. The jews I've known (albeit reformed, which are the vast majority) have all been very socially liberal, both in manner/permissiveness… even the rabbis. Given their long period of study of the old testament, clearly they feel its consistent with the teachings.

If the supposition is based on simply another interpretation of the old testament, one could question why christians vote republican.

The new testament is full of forgiveness and an abhorrence for tragedies such as war. The bible is also very sympathetic to the poor, and skeptical of the rich, yet republican economic policies do not reflect this ethic.

It's really based on very shaky rationalizing, and a supposition that one's view of religion and religious tenants is superior to the rest.

David: Yep. I'm glad somebody caught that!

History does a lot of explaining. Space is too small, so a few highlights:

1. Jews in America rapidly shifted from Old World to New and embraced liturgy and the underlying philosophy that looked toward reforming practices to meet the challenges of this world, both temporal and spiritual. You'd need to understand the history of Jewish liturgy in America.

2. Jews came from a world suffused with injustice, having only recently been let out of locked ghettoes, having only been allowed to be citizens anywhere since Napoleon. This history dramatically affected attitudes toward social issues in America.

3. Judaism is a mix of individual and community and in a world in which Jews sought to escape the lines which held them in it made sense to draw new lines that revolved around word – thus unions – and class. This finds support in many strands of Jewish learning, not merely liberal sources. In fact, the more "Orthodox" differ more in how little they engage in the outside world than in the traditions of justice – meaning that if they engage less, then the outside world has its own problems which are not then Jewish problems. The question is more the extent to which that Jewish community participates in greater society, not the ideals they hold. A simple statement is that if you believe you are an American, that your community is America, then how can you not work for healthcare for all in your community? A devotional Jew would define community narrowly, while other Jews would define community broadly – and, as I do, wonder what happened in this Christian nation to the concept of charity.

4. With respect to Civil Rights, it was not a great stretch in modern times to equate black suffering with the Bible stories of Pharaoh. "Let my people go" again tends to separate the devotional Jews who avoid the world at large.

Moving away from Judaism, there is no way one can argue sensibly that voting GOP means voting for a better economy. That isn't born out by history. Wasn't Hoover President during the Great Depression? Weren't Democrats in power in the 1960's when times were good?

As a note, I used to vote GOP but no longer do because the party now believes in imposing morality – when it used to be about not imposing morality – and because the economic policies of lower marginal tax rates and deregulation have been a fiscal disaster that haven't generated jobs, raised incomes (for all but a narrow slice) or generated more revenue, etc.

Its a small sample size, but some Jews have explained to me that they vote for Democrats because they think the Republicans want to institute a theocracy in the US. I used to think this was paranoia, but haven't been so sure recently.

Visible minorities, and not just in the US, have a tendency to vote as a block. Andrew pointed out the same dynamic is at work with Mormons. This makes sense as a strategy for minorites to maximize their influence and compensate for, well, being minorities. The dynamics of voters independently deciding to act this way are fascinating.

As urban voters, Jews have historic ties to the Democrats and that is often enough. A Democratic adminstration recognized Israel (incidentally I don't think uncritically supporting bad Israeli policies is "good for Israel" but that is for another discussion). Jewish culture puts a particular value on education, which is not exactly a priority with the Republican Party. Republicans are pretty consistent in wanting to tax the New York City area and redistribute the money to more rural parts of the country, which should give anyone living in that area pause even if they agree with the Republicans on other issues. I'm not sure that this is such a difficult question.

Why don't more Jews in the US vote more for Republicans? Keep in mind that non-Jews in Israeli elections rarely vote for Likud or the Jewish religious parties.

The Atlantic Monthly recently drew up a list of the 50 most influential pundits in the U.S. Half of them are Jewish by ancestry.

http://isteve.blogspot.com/2009/09/demographics-o…

So, even though Jews make up only 3% of voters, they are, by far, the largest single bloc of opinion-molders.