Dan Lakeland writes:

Apropos your recent posting of the Churchill/Roosevelt poster, there has been a bit of a controversy over the effect of smoking bans in terms of heart attack rates. Recent bans in the UK have given researchers some plausible “experiments” to study the effect on a larger scale than the famous “Helena Montana” study. For example, this.

On the other hand, when looking for info about this to follow up your poster I found a variety of usually rather obviously biased articles such as this one. But that’s no reason to ignore a point of view if it can be backed up by data. The second link at least attempts (poorly) to display some data which suggests that an existing downward trend could be responsible for the reductions, and if poorly done the statistical research could have missed this.

Have you looked at the statistical methodology of any smoking ban studies? it seems like an area ripe for Bayesian modeling, and could be a subject along the lines of the fertility and beauty more girls/more boys research that you recently meta-analyzed.

My reply:

Yes, I imagine that some people have looked into this. I would guess that a smoking ban would reduce smoking and thus save lives, but of course it would be good to see some evidence.

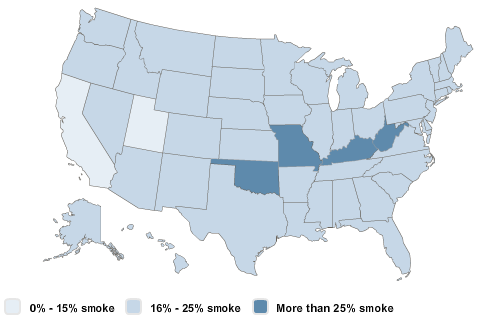

Smoking behavior is a funny thing: It can be really hard to quit, and I’ve been told that the various anti-smoking programs out there really don’t work. It’s really hard to make a dent in smoking rates by working with smokers one at a time. On the other hand, rates of smoking vary a huge amount between countries and even between U.S. states:

And smoking bans might work too. Thus, smoking appears to be an individual behavior that is best altered through societal changes.

One point I failed to mention, is that much of the claimed effect of smoking bans has been in terms of broadly reducing the rate of secondhand smoke.

I think this is perhaps the most controversial, but also potentially the most important effect, since these days much less than half of the population are active smokers (as per your map) but if smoking bans significantly improve the health of the ~75-80% or so that don't smoke that's a huge win for society.

The second article Lakeland quote's has a link to a NBER wp that's really interesting.

"publication bias could plausibly explain why dramatic short‐term public health improvements were seen in prior studies of smoking bans." p. 23

http://www.nber.org/papers/w14790.pdf

This makes me wonder, what would the smoking map look like over time?

Has the distribution of smokers changed?

Has the number of smokers by region changed over time and how?

If you can map those historical figures, that would be interesting to see too.

Thanks.

Why must people ask about health effects? They are at most a pleasant positive aftereffect.

The effects of smoking bans are to make public spaces more appealing to the 3/4 of the population that does not smoke. Food tastes better when there is no smoke. Hanging out at the pub is more fun when there is no smoke. Going to bad rock shows does not leave every shred of your clothing reeking of tar and nicotine any more.

I am pretty sure smoking bans always function as intended. They make life better, even for most smokers (well, most of the ones I know).

wcw.

It was not always the case that the majority of people didn't smoke, which is why the health effects were historically important at least. When 75% of the country wanted to smoke, inconveniencing them made sense because the non-smokers were being harmed not just inconvenienced.

These days smoking bans make sense for lots of reasons, but it's all the more interesting if there really are significant benefits with respect to heart attacks due to eliminating *secondhand* smoke, even though only 15 to 25% of the population smokes.

At least in the US, Daniel, the proportion of adult smokers peaked at 45% in 1954.[1] I haven't seen data on earlier years, but if you have, please share. I'd be astounded if 75% of the adult population were self-reported smokers at any point.

[1] http://www.gallup.com/poll/109048/us-smoking-rate…

Some data here (for males);

http://chestjournal.chestpubs.org/content/111/5/1…

Looks like the males data from Freddy is significantly higher than the overall data from Chris.

In any case, even 45% is at least a binary order of magnitude larger than the current trends in much of the country (say 15 to 20%). And with the large number of wartime smokers who probably weren't polled, I'd bet the 1940's data was biased low.

Interestingly just yesterday this story hit the news: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/16/health/16smoke….

This report seems to be exactly the kind of thing that could benefit from some external statistical review.

Daniel: second opinions are always a good idea – but the committee did have two very capable statisticians Francesca Dominici and Stephen Fienberg with lots of expertise in meta-analysis of published studies …

Keith

Keith, thanks for the additional information. One thing that concerns me is that they did not estimate the size of the effect. I side with Andrew's statements that there's always SOME effect, so I see the role of statistical analysis as specifically to help find the plausible size of effects.

From this report:

http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2…

"While the committee found strong evidence of this association, the evidence for determining the precise magnitude of the increased risk-that is, the number of cases of disease that are attributable to secondhand-smoke exposure-is not as strong. The committee therefore did not estimate the size of the effect."

So the results are certainly not as satisfying as I would like. Though I can understand the political reasons to avoid an official report with some kind of Bayesian posterior interval, that doesn't mean we shouldn't calculate one amongst friends :-)

A British comparison:

"In Britain in 1948, when surveys of smoking began, smoking was extremely prevalent among men: 82% smoked some form of tobacco and 65% were cigarette smokers. By 1970, the percentage of cigarette smokers had fallen to 55%. From the 1970s onwards, smoking prevalence fell rapidly until the mid-1990s. Since then the rate has continued to fall slowly and in 2007 around a fifth (22%) of men (aged 16 and over) were reported as smokers."

See

Source was

http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/type…

Daniel: I don't know the specifics here, but its not that unusual for a "well done" meta-analysis to conclude that there is not any or enough credible evidence to support estimation or testing of effects – i.e. even spare your friends from the almost surely misleading posteriorS.

But the materials to re-do the meta-analysis should be public, hopefully even given conveniently somewhere, and so if its really of interest to you – feasible to get a relevant second opinion.

If so I would suggest a Bayesian approach given in a paper by Robert L. Wolpert and Kerrie L. Mengersen http://ftp.stat.duke.edu/WorkingPapers/02-15-STS….

Keith

Several points:

1) Some very well done critical analysis of the IOM, Glantz, and Meyers meta-analyses can be found in the October 15th through 18th entries by Dr. Michael Siegel at:

http://tobaccoanalysis.blogspot.com/

as well as in the commentaries afterward.

2) The very large RAND/NBER analysis showing no widspread health benefits from smoking bans is very well done, but it was presaged by another similarly large study that I did with Missouri researcher Dave Kuneman several years ago. The full story of that study can be found in this American Council on Science and Health article:

http://www.acsh.org/factsfears/newsID.990/news_de…

3) The biggest and simplest problem with these meta-analyses is that they have taken a dozen small studies which have virtually all been found to have serious defects and used them to build one large "Grand Study." The problem is that if you take a lot of little pieces of trash and mound it up into one large mound of trash… it is still trash, not a Crystal Castle.

Michael J. McFadden

Author of "Dissecting Antismokers' Brains"

Keith wrote, " I don't know the specifics here, but its not that unusual for a "well done" meta-analysis to conclude that there is not any or enough credible evidence to support estimation or testing of effects"

Keith, that's quite true, and the RESPONSIBLE approach in that case would be to tell the truth and inform the media that they were not able to meet the basic criterion of statistical significance to say anything about smoking bans… much less be able to say anything about secondary smoke exposure.

Instead we see story after story with quote after quote from supposedly responsible authorities and organizations presenting the study as showing the need to protect people from the deadly wisps in the air.

Those "authorities" should be removed from their positions and those organizations should have whatever tax support or breaks they currently enjoy removed immediately. Lying to the public, *terrorizing* the public in reality, should not be countenanced.

Michael J. McFadden

Author of "Dissecting Antismokers' Brains"